Before we get into today’s newsletter: in this Jewish holiday season, I’m wishing a gut gebentsht yor — a good, blessed year — to everyone reading this. Thanks for tuning in; I’m grateful to have you here.

I’ll keep this preamble relatively quick. In the last installment, I introduced the poet Rokhl Korn with her poem “Elul.” You can check that out, if you missed it, for some information about her life, or head to her entry in the YIVO Encyclopedia if you want to go a little bit deeper. And I love this speech Korn gave in Montreal, in 1977, wonderfully translated by Mikhl Yashinsky. There she discusses her poetic origins, and muses on the nature and origins of poetry in general. Poetry, for Korn, “is a magical transporter through time and space because it manages to contain the present, the past, even the future.”

Korn in 1970, via the Jewish Women’s Archive

There are too many highlights from Korn’s speech to share here; I’ve tried to select excerpts, and just ended up copying and pasting the whole thing, so I encourage you to check it out for yourself. (Ok, another highlight, because I can’t resist: the poet “sets words as witnesses to the eternal struggle between justice and injustice, between purity and impurity. At the same time, the poet is the executor of an estate, who comes to collect the debts that the people owes to itself.” Amazing stuff!)

We’ll look at another poem by Korn today, but before we take off on that “magical transporter through time and space,” I have an exciting learning opportunity to share.

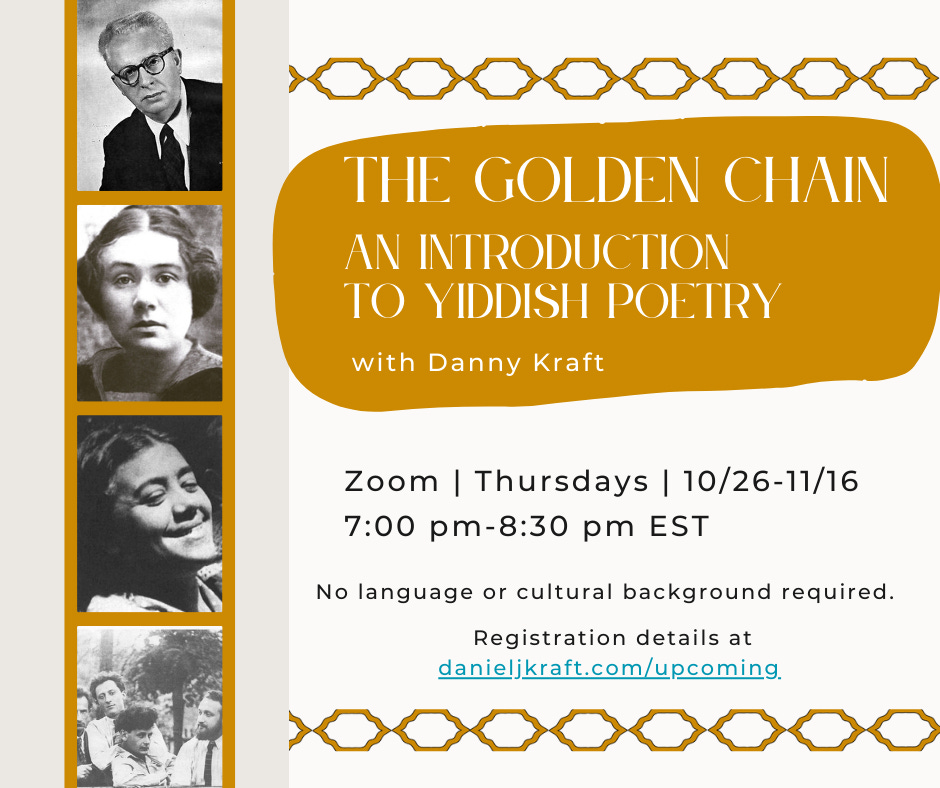

On four Thursday evenings, starting 10/26, from 7:00-8:30 pm EST, I’ll be teaching an online Introduction to Yiddish Poetry course. If your reading here has piqued your interest, and you’d like to spend some time talking about Yiddish poetry together via Zoom, I’d love to have you there. No knowledge of Yiddish or cultural background is required.

Together we’ll read and discuss great Yiddish poems and writers, exploring the themes, contexts, and concerns of modern Yiddish poetry and their meaning for our own lives and labors.

The cost is $90-180, on a sliding scale. If you’d like to participate but the lower range of this would be prohibitive, please email me; no one will be turned away. And if you’re already a paying subscriber to this newsletter, please feel free to ignore that scale and pay whatever you’d like.

To register, please send payment to my paypal (djkraft13@gmail.com) or venmo (@danny-kraft-1) — in the payment message, include the email address where you’d like to receive the link, recordings, and other information. Don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions, or head over to my website for more details.

Now, without further ado, let’s get into today’s poem. It comes from the same 1948 book, Heym un Heymlozikayt (Home and Homelessness) that included “Elul.” But while “Elul” was written in 1943, when Korn was a refugee in Fergana, Uzbekistan, this poem was written between 1939 and 1941, when World War II had already broken out, but the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union had not yet forced her to flee her home.

Dream

For H. Leivick - With Deepest Admiration

In wintry, white nights,

when sharp winds howl and weep and laugh,

the moon slashes a new path through the snowy void

with her pointed horn,

so that I won't get lost on way home

from distant world-journeys.

I stand before my old, straw-covered house a long time

and throw a bale of hay under the rotting fence,

for bending does and brown hares

chased by hunger from the deep forest.

My tear falls—and starts to blossom

the dry, rustling branches of the antlers

on the lean deer-heads,

and blooms with snowy stars,

like thorns that flower white each spring.

I stand and wait—

maybe nearby will glow the amber-gold gaze

of my cat, who ran into the woods

in those days when I abandoned my home,

and nobody has seen her since.

I stand and wait—

maybe the shadow of my grandmother Chaya will slip through

when she goes with her footstool and pail out to the barn,

to milk her cow, Flower, the faithful one,

who trusted no one else

until her death.

I stand and wait—

perhaps he will suddenly arrive here from the other world

with his winking, grinning eyes,

one pitch-black and the other dove-gray,

on a night-quiet rendezvous

with a young, hot-blooded woman.

And against him will come my aunt Dvoyre,

blocking his way with her wide shawl

that flies around her shoulders like a dark stream.

I stand and wait—

I hear some kind of chase , a howling, a scream,

the forest at night is so vast and near—

perhaps it is running up to my grandfather's house

to reclaim the three pine trees?

Shh, someone calls to me, someone knows on the windowpanes,

I remember my father's thin hand—

he holds his bearskin coat wide for me:

"child, come in, day breaks and you are cold."

I am so small, and the coat—just look, how big it is!

He smells so good, I can't recall what that smell is from,

I want to remember...

But on the gray eyelash of the sky

the pale yellow tear of the sun already hangs

and drips onto the thin, fresh tracks

of doe and hare

who look for summer and grass

in the sad, snow-covered paths—

and in my dream,

which comes to meet them.

Another poem I find extraordinarily moving. (And it’s dedicated to H Leivick, whom long-time readers will recognize as the author of the very first poem I shared here, the one that kicked off this whole project.)

I’m thinking again of Korn’s idea that poems are “magical transporter[s] through time and space.” We see that here, as the dead come back to life and the poet inhabits, both briefly and through her eternal words, her “old, straw-covered house,” built by her grandfather. But to “time and space” I would add that the poem transports us through the borders between the dream world and the waking world, between conscious experience and the realm of the unconscious.

The poem is a dream, of course—that’s its title. But the borders of its dreamscape are porous. By the end of the poem the doe and the hare seem to me to have an objective existence as they look to forage through a long winter. They belong to the world of wakefulness, things and hunger and logic’s exigencies, as they leave the forest to find food. Nevertheless, they are swept into the immaterial world of the poet’s dream.

That closing gesture hits me every time. Where do the doe and the hare look for food? In the snow-covered paths that winter renders barren, and in a dream. Suddenly the distance between dreaming and wakefulness collapses: these creatures can move in and out of each as they search for sustenance.

I’ve heard it said by a few different people that art is a form of public dreaming. In the case of this poem, that’s literally true. In the dream, as in the poem, a tear’s falling can cause antlers to bloom. In the dream, as in the poem, creatures can leave the woods to forage through your consciousness.

We’re not so different from this hare and this doe. We, too, leave the snowy paths of our mundane lives to look for sustenance in the dream world artists offer us. How do they do it?

Korn offers us a clue into her own process through this poem’s refrain: “I stand and wait.” She does not rush into activity or interpretation. She simply waits, and listens, and is open to whatever might come, however strange or frightening or irrational it reveals itself to be. Korn discusses this as well in the 1977 speech I mentioned above. To be a poet, “One must be patient. One must wait.”

In that speech Korn also describes her rural childhood: “I would sit on the daybed in the kitchen and look through the window on the snow-covered expanse, and especially at the orchard, with its small, young sour cherry trees, their crowns just barely peeking out over the fallen snow which had formed a fortress around our house. And I would read a dark calligraphy etched into the white snow, the tracks of wild animals that had emerged from the forest to pay us visits in the night: foxes, hares, does, and sometimes even a wild boar.”

The “dark calligraphy” of the nocturnal animal tracks against the white snow: Korn’s language, even in prose, is vivid and precise. In adulthood she recalls her child’s sense of reading the magical, otherworldly writing left for her by non-human creatures. In this poem, she invites us into that experience of a child’s dream-like communion with “does and hares.”

Children dream and daydream shamelessly. But as Freud puts it: “the adult, on the other hand, is ashamed of his daydreams and conceals them from other people; he cherishes them as his most intimate possessions and as a rule he would rather confess all his misdeeds than tell his daydreams. For this reason he may believe that he is the only person who makes up such phantasies, without having any idea that everybody else tells himself stories of the same kind.” (That’s from Freud’s 1907 talk turned essay, “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming,” in a 1930 translation by Melvin Rader.)

I’m not interested in going into Freud’s whole theory of the relationship literary art and dreams, daydreams, reveries here. But I do think that, at least in this passage and its relevance to Korn’s “Dream,” he’s on to something essential. She has the courage to refuse any shame for continuing her childhood reveries into adulthood and publicizing them, and she has the artistry to make those reveries beautiful. We don’t need Freud’s fancy theories to connect poetry to the experience of childhood daydreams; we find that in the poem itself, when Korn returns to the people she remembers and to the physical sensations of being a little girl, engulfed by her father’s giant coat.

She stands and waits and lets the visions come, and invites us onto the “magical transporter” of her poem so that we, too, can join her at the junction of dream and waking reality.

(As always, there’s so much more I want to say about this poem. Korn remembers how her father smelled when she was young, and “can’t recall what that smell is from,” and “wants to remember.” I love this moment of crystallized tension between memory and forgetting. And the incredible strangeness and lucidity of her images: “the gray eyelash of the sky.” What a poem!)

Today’s art painting: Edouard Manet’s 1870 “Effect of Snow on Petit-Montrouge”

I always like a good trip into a liminal place— sleep, dream, memory. Lovely.