The world continues to be a difficult place. Is that a trite, banal, irrelevant thing to say? Yes, of course; nevertheless, it’s true, and due to distractions from both global and personal events I haven’t had as regular a newsletter routine here as I’ve wanted for a while. Thanks for bearing with me.

I know that many of my readers continue to be personally impacted, directly or indirectly, by the terrible violence and fear unfolding in, and rippling out from, Gaza and Israel. (But note how I too fall into euphemisms: “personally impacted.” What does that actually mean? And what would be better to say? I confess that I’m not sure. Distressed? Distraught? Grieving?) I hope you’re hanging in there, and finding ways to care for yourself. I hope that I only have good things to find apt poems for soon.

But in the meantime, here we are. For a different and challenging Yiddish literary perspective on this war and its context, I recommend Shachar Pinsker’s new translation of Avrom Karpinovitsch’s 1951 short story “Never Forget,” published recently in In Geveb. It describes a Holocaust survivor who, just days after arriving in a nascent Israel, is thrown into the fight for Israel’s independence. No spoilers but, as Pinsker writes, “This story raises questions of trauma, memory, and violence, of revenge and empathy, without giving clear answers.”

In the meantime, if you’re in the mood for a change of scene, and want a little bit of kitschy Yiddish levity, here’s a clip from the 1982 Yiddish musical movie, Az Men Git Nemt Men. I’ve shared another song from this once before here, I think, but it remains a good palate cleanser in the midst of some unavoidable heaviness.

For today’s poetry installment, and in my continuing quest for poems that can respond meaningfully to this moment, we return to to Jacob Glatstein. His words provide the name for this newsletter, and I’ve already shared poems of his here, here, and here. This poem, “God is a Sad Maharal,” was first published in his 1943 collection Gedenklider (Remembrance Poems.) I’m sure I don’t need to clarify what that year means in the Jewish 20th century, what then-current events Glatstein was responding to.

I’ll say more about this after the poem, but if you’ve never heard of the “Maharal” before, this is a traditional Hebrew acronym for Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the 16th-early 17th century rabbi famous for, among other things, creating the legendary Golem of Prague.

God is a Sad Maharal God is a sad Maharal. A beam of His goodness falls on a dark world. He sits beside the well of His wonder and throws in heavy stones. Listen. He is unhappy. Golem-like punishment is out of His control— it has overpowered Him. Every sigh is warranted. Every scream blazes in the empty sky. Eternity charges towards the most deranged finale. God is a sad Maharal. God is a sad Maharal. The sound of the shofar inspires Days-of-Awe-trembling in the woods. The heart of the Great Punisher is broken and bitter. Not even He created so much brokenness. He feels ashamed and minuscule, like every terrified Jew. Silently He'll sneak into the synagogue. Wrapped in a tallis He will stand in the vestibule, like a penitent, and He will tear the dark heavens apart with His weeping. A wind blows an autumn shiver. A tree sways. A leaf falls. God is a sad Maharal.

The Maharal was, in that early modern way, many things: a mystic, a theologian, a Talmud commentator, a mathematician. He was also, the legend goes, the creator of the Golem of Prague, a humanoid figure he brought to life from clay, using his mystical powers and esoteric learning. Different versions of the story exist, but this golem protected Prague’s Jews from antisemitic violence, until the Maharal removed its lifeforce, and stored its body in the attic of the synagogue. (Where it remains, perhaps, to this day—if you find yourself too quick to dismiss this as a legend, you might be interested in the debate around this golem’s historicity that still occurs in some Jewish communities.)

So what does it mean that God is a sad Maharal? On the most basic level, God is a creator, like the Maharal; they both use the esoteric secrets of existence to fashion life out of clay or dirt. That’s what we are, after all, according to certain Jewish traditions: mystically enlivened earth.

But unlike the Maharal, at least depending on the particular legend, God’s golems—us—are absolutely out of God’s control. God creates us, and we create a brokenness that God could not conceive of. You don’t have to believe in any God to empathize with the grief of a God who made humanity, and then had no choice but to look in horror at the suffering we cause.

Glatstein did not, however, write: “God is a Sad Creator.” There’s something fascinating and subversive about this metaphor’s comparison of God to an actual, historical human being. Maybe it’s just about the story of the Maharal making his golem. Or maybe there’s more to it than that; I’m really not sure. If anyone has ideas, especially anyone with more of a background in the Maharal’s life and teachings, I’d love to hear them.

Regardless, like all metaphors, this one cuts in both directions. God is a kind of Maharal, and the Maharal is a kind of God. Yes, of course, that’s true because of their shared creative capacities. But we can also extend it further: God is like a sad human being, and a human being, in turn, is like a sad God. This poem makes me think of Emerson’s quote: “A man is a god in ruins.” And here we are, we ruined gods, making a ruin of this world.

(A closing note: I don’t have much that’s smart to say about it, but I absolutely love and am very moved by this poem’s image of God sneaking into the back of the synagogue, not even entering all the way or joining the congregation, and tearing heaven apart with his weeping prayer. Why can’t or won’t God enter all the way into the synagogue?)

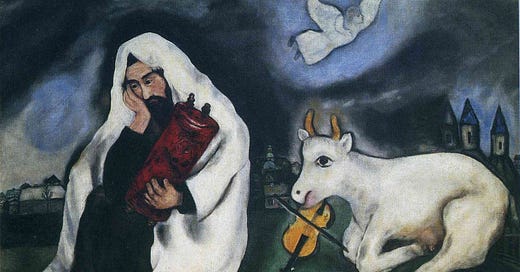

Today’s art pairing: Marc Chagall’s 1933 “Loneliness”