Let us Learn... by Melech Ravitch

With a digression about Leonard Cohen

Way back in April, I shared a lovely, short poem by Melech Ravitch, along with a rough outline of his fascinating life, and this wonderful photo:

That’s “Di Khalyastre” - the Gang - a group of avant-garde Yiddish writers based in Warsaw. Peretz Markish, whom we’ve also met through this newsletter, is in the middle; our subject today, Melech Ravitch, is second from the right.

Before we dive into our content, however, I’m excited to share an upcoming zoom opportunity for all paying subscribers. On Tuesday, 1/31, at 7 pm eastern time, I’ll be giving an informal talk on the history of Yiddish literature. If you’ve ever wondered where Yiddish came from, how it became a literary language, and how it developed into the incredible poetry I’ve been sharing, this is your opportunity! I’ll send a zoom link to paying subscribers before the 31st, so if you’d like to join us I hope you’ll consider a membership option. (And if you’d like to come, but aren’t able to pay the subscription fees, please let me know as well and I’m happy to include you!)

In my earlier synopsis of Ravitch’s biography, I mentioned that he crossed paths with Leonard Cohen during the many years he spent living in Montreal. What did I mean that they crossed paths? In 1964, Ravitch and Cohen were both panelists on a symposium of Jewish-Canadian writers. (You can find audio of the whole symposium here. The young Cohen is fiery, polemical, iconoclastic; his rants on this recording constitute one of my favorite primary sources in modern Jewish culture, but that’s an essay for another time.)

When Ravitch expressed his concerns that Jewish writers who wrote in English risked assimilating their writing away from Judaism, Cohen responded sharply: “The language of my spirit is English. Mr. Ravitch manifests an interesting nostalgia for Yiddish and Hebrew, but if he believes that the future of Jewish emotion and spirituality resides in those two languages, he must relegate the entire North American Jewish experience to the outer limits.”

In some important ways, I don’t think that Cohen’s wrong. But it seems laughable now, given modern Hebrew’s thriving literature, to dismiss Ravitch’s concerns as “nostalgia.” And though as a Leonard Cohen disciple I hate to say it, there’s also a cruelty in his sneering description of Ravitch’s “interesting nostalgia” for Yiddish. Cohen made these comments just two decades after the Holocaust, at a time when Ravitch and every other Yiddish writer of his generation was struggling with a complicated mix of grief and obligation and hope and despair for their native language, its speakers, and its civilization.

(I’ve been fascinated by this symposium for several years; thanks to this recent article at the Forverts for putting it back on my mind.)

Much more could be said about this, of course, and I have to wonder what motivated Cohen’s condescension. A sort of Freudian need to claim his own place in Jewish literature by belittling an elder statesman, perhaps? But without further ado, let’s get to today’s poem.

Melech Ravitch wrote this in July, 1963, less than a year before that symposium with Leonard Cohen and others. Though there is perhaps some nostalgic romanticism, there is no linguistic nostalgia here; the vibrancy of Ravitch’s writing shows how reductive and absurd Cohen’s snide remark about his “interesting nostalgia for Yiddish” really was. I’ve taken the below from Ravitchs’s 1969 collection, עיקר שכחתי.

Let us Learn…

Let us learn from the creatures in the forest

to live with the course of the sun for as long as it shines.

To live like life itself: now, in this moment,

without knowing even that today is today.

Let us learn from the birds of the sky,

flight-singing, sing-flying; isn’t everything flight and song?

Let us learn to live with thin heads,

colorful, devoid of any thoughts.

Let us learn from the trees and the grasses

to release our roots into mud, into water, around stones.

Let us learn not to think, as absolutely as the plants.

On the whole, is there anything in this world to understand?

Let us learn from God, from God, if you will,

who withers life and grows it, demolishes things and builds them,

who is eternal because He knows the secret of secrets,

the simplicity of simplicities: no distinction exists between life and death.

And no distinction exists, all the more so, between death and life,

and no distinction between hiding and revealing.

Either way, all was and all will be—YHWH—

and no distinction, no border, separates humanity from God.

A confession: I had a sort of inarticulate idea, several months ago, that this poem would be a good reading for the New Year, so I made a note to myself to revisit it this week. And now I can’t remember what I was thinking, so I’ll try to speculatively reimagine why I jotted down that this was a “new year’s poem.”

Perhaps I had in mind this poem’s insistence that the passage of time is a lie, that “no distinction exists between life and death,” and therefore that every fading away is simultaneously a coming into being. Good advice for our culture’s obsession with letting go of the past, with novelty, with transformation. “New year, new you,” the slogan claims. Ravitch’s poem might respond that there’s no such thing as a “new” year, and that if we can get out of our heads enough we’ll understand that everything is always what it’s been forever: the endless process of being called God.

Or maybe I intended Ravitch’s rejection of thinking as a kind of new year’s resolution for myself. I’m someone who spends a lot of time planning, analyzing, worrying, imagining, projecting, etc., on and on. The mental chatter never seems to end. What would it mean to learn from animals and plants how to let some of that thinking fall away? What ways of being in the world would that enable?

It’s a rich poem, in part because it asks us, its readers, questions. “Isn’t everything flight and song?” “Is there anything in this world to understand?” These aren’t rhetorical; I think that Ravitch really wants us to think about them, to carry them with us. But then what? Yes, I’d like to say; there are things to understand. But if I sit with the question longer, I come to a place of confusion and wonder. The things I think I understand only incite more questions. Because of this, the poem gives me a profound and simultaneous sense of humility and grandeur.

On the one hand, according to Ravitch, nothing separates me from God. And on the other hand, at the same time, I don’t really understand a thing, and I should let my intellectual pretenses go in order to learn from those creatures—plants, animals, birds—which I habitually think of as less advanced, but which in fact have so much to teach me.

(Though it takes a different approach, this poem also puts me in mind of a brief prose passage I’ve always treasured from W.B. Yeats: “We can make our minds so like still water that beings gather about us that they may see, it may be, their own images, and so live for a moment with a clearer, perhaps even with a fiercer life because of our quiet.” )

As always, I enjoy hearing your responses, by email and in comments below. Whatever I was thinking when I identified this as a new year’s poem months ago, and however illusory the passage of time may or may not be, I hope that we can all find some opportunities for flight and song in 2023.

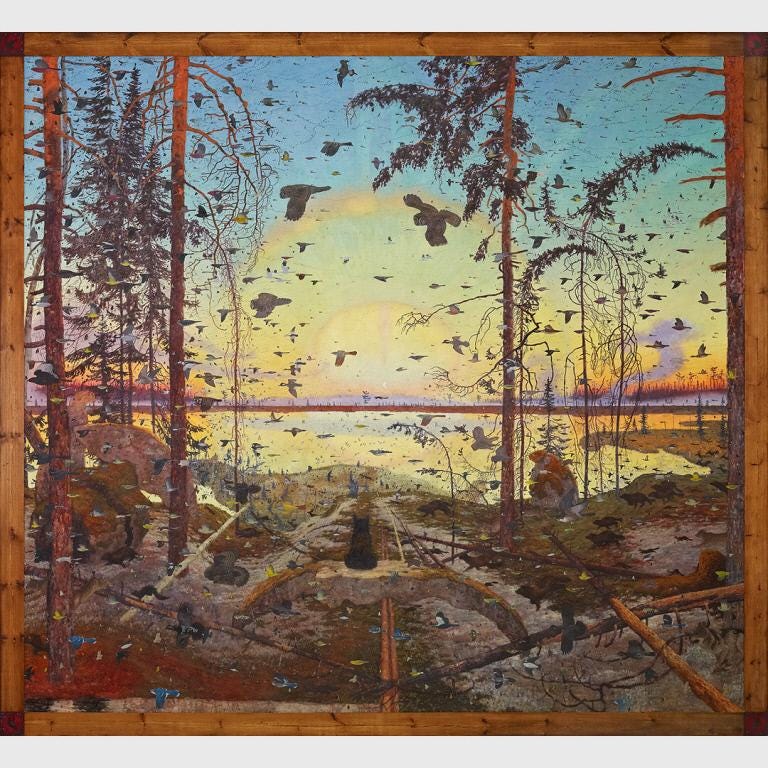

In conversation with this week’s poem, here’s Tom Uttech’s painting, “Enassamishhinjijweian.” It’s 103x112 inches—I’m grateful to have seen this painting in person!