The title of this newsletter takes its name from a 1961 collection by the great Yiddish modernist—many would say the greatest Yiddish modernist—Jacob Glatstein. But I haven’t yet shared any of his poems, a problem which I’m happy to correct today.

Glatstein was born in 1896 in Lublin, Poland, and received both a traditional religious and a modern secular education. At age 13 he traveled to Warsaw to share his writing with the luminaries of that city’s Yiddish literary salons, and five years later he emigrated to New York City, where he immediately began publishing in the Yiddish press.

He worked in Manhattan’s sweatshops, and for a time studied in the law school at New York University. But his true love was writing, and in 1920 he became one of the founders of the modernist Yiddish literary group, In Zikh, with which Celia Dropkin was also affiliated.

His poems of the 1920’s were radical attempts to assimilate modernist experimentation into Yiddish, and Yiddish into modernist experimentation. Richard Fein writes that these “poems were a product of the Jazz Age: they contain the jagged realities of post-World War I sensibilities, a world in which art for art’s sake was rejected and aesthetic endeavors were open to revolutionary new approaches.” Free verse, imagism, neologisms, near-nonsense; Glatstein used the whole experimental toolbox in his writing, and “made New York the center of modern Yiddish poetry.”

The Holocaust, of course, changed everything. In the 1930’s he traveled back to Poland, and wrote two prescient novels about his trips there. During and after the War, Glatstein became less concerned with his literary experimentations, and more concerned with responding to and expressing the upheavals and traumas of Jewish modernity.

By the time of his death in 1971, his poems, fiction, essays (he published well over 500 critical essays!) and cultural activism had established him firmly as one of 20th century Yiddish’s most important figures. So there’s a lot more to say about him, and I hope to dedicate some more space to Glatstein in upcoming editions of this newsletter.

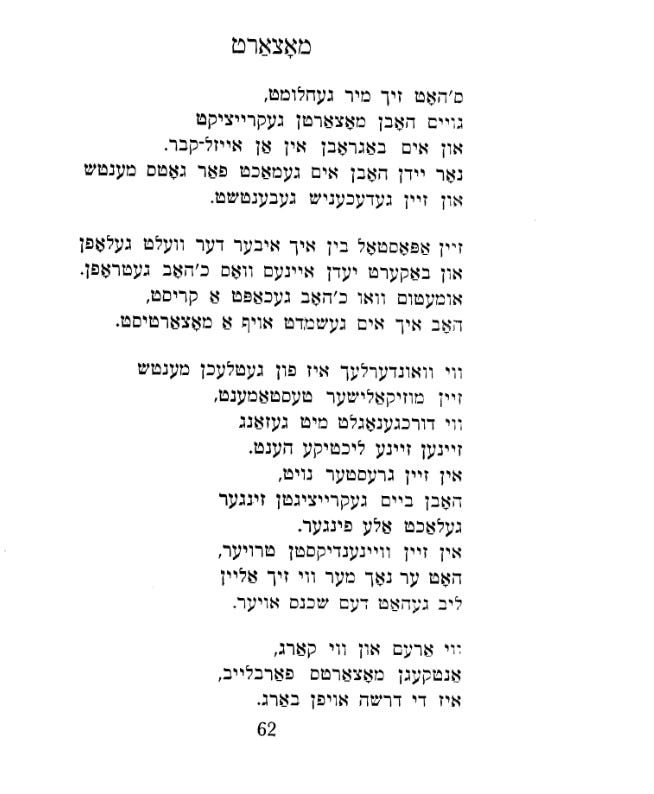

Mozart

I dreamed that the gentiles

crucified Mozart

and buried him in an unmarked grave.

Only the Jews saw Mozart’s holiness

and sanctified his memory.

As his apostle I have traveled through the world,

accosting everyone I meet.

Wherever I can catch a Christian

I convert him to a Mozartist.

How wondrous is this divine man’s

musical testament, and how nail-pierced

with song are his illuminated hands.

Within his great despair, all the crucified singer’s

fingers laughed. In his deep grief

he loved his neighbor’s ear

more than he loved himself.

How paltry, how impoverished,

compared to Mozart’s gospel,

is the Sermon on the Mount.So much to say about this strange and lovely little poem. I shared it without context, but I wonder how our reading of this poem changes when we learn that it was published in Glatstein’s 1946 book Shtralendike Yidn (Radiant Jews), alongside many devastating Holocaust elegies. That collection is filled with poems of grief and rage—rage towards humanity, and towards God.

With this background in mind, “Mozart” reveals itself not only as a witty, surreal celebration of the great composer, or a tongue-in-cheek comparison between Mozart and Jesus. In my reading it is also a polemic against Christianity, a defense of Judaism’s spiritual relevance in the aftermath of genocide, and an argument for the sacred value of art over Christian moral teachings.

Or perhaps I should have written, “for the sacred value of art over all moral teachings.” It’s not clear to me how far Glatstein’s critique here goes.

It’s striking and, to me at least, moving, that this poem centers around an Austrian composer, a baptized Christian, whose legacy was part of the German cultural milieu which led to the rise of Nazism. I might have expected him not to celebrate a German-speaking, Christian artist, especially in such a polemical poem published in 1946.

I have the sense that Glatstein identifies with his presentation of Mozart here: his description of the composer’s fingers laughing through his despair, laughing with the joy of artistic labor and the creation of beauty, could also describe Glatstein himself, in New York City, grieving for the destruction of his hometown and its culture, while letting his fingers delight in the work of writing poetry.

And I love that he calls Mozart’s music a gospel. Gospel, of course, comes from the Greek for “good news.” What is great art if not a revelation of the good news that whatever chaos and suffering and degradation exist, these can be transformed into some kind of structure, into some kind of beauty?

Addendum:

I’ve dithered over sending this out because, as soon as I wrote the above, I started to wonder whether I had the poem completely wrong. What if there’s a deep irony at play here, and Glatstein isn’t simply arguing for the superiority of Mozart’s gospel over Jesus’?

According to this alternative reading, the last stanza’s claim that Jesus’ gospel is paltry and impoverished does not mean that it is inferior, but only that it is weaker, and less able to inspire genuine disciples, compared to Mozart’s music, which is powerful and stirring but dangerously amoral?

A fuller exploration of my questions about this poem and its complexities, its ironies, its critiques is, alas, beyond the scope of this newsletter, and beyond the time I have right now, so I will just leave this here. I’ve deeply appreciated so many of your responses to these poems, and if you have thoughts about how to read “Mozart” I would love to hear them.