The last edition of this newsletter introduced the poetry of Jacob Glatstein, and I’m happy to share two more short poems of his this week.

Since I already gave the broad outlines of his biography, I won’t add much today, except to include this provocative and moving interview excerpt from 1955, in which Glatstein discusses “the mission of the contemporary Yiddish poet,” and that mission’s relationship to the Holocaust:

The first poem below, “Smoke,” comes from Shtralndike Yidn (Radiant Jews), the same 1946 collection that included “Mozart.” The second was published a decade later, in the new poems section of Glatstein’s collected poems from 1919-1956.

Smoke

Through crematorium chimneys

a Jew spirals upwards towards the Ancient of Days.

When that smoke disappears

his wife and son curl upwards too.

And in the heavenly heights

sacred smoke weeps, longing.

God, up there where you are,

even there are we gone.

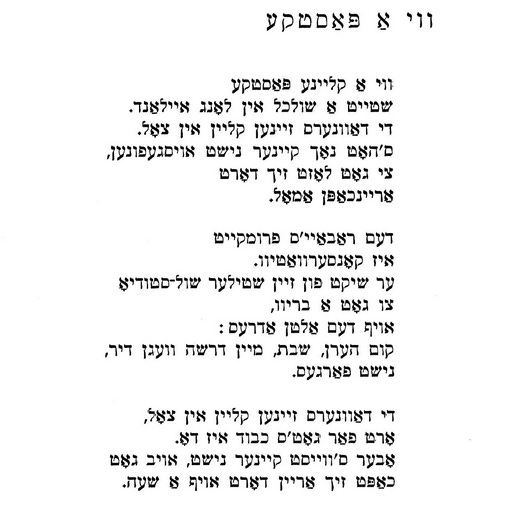

Like a Trap Like a little trap stands a little synagogue on Long Island. The congregants are few. No one can tell if God sometimes drops by. The rabbi is Conservative. From his quiet synagogue study he mails God a letter at the old address: Come hear my sermon about you, Shabbos, don't forget. The congregants are few, there's room for God's glory. But no one knows if God will drop by for an hour.

I’ve been wanting to think about these poems alongside each other for some time now.

Both of them are concerned with the relationship between absence and presence: the absence and presence of God, and the absence and presence of the Jewish people. In the first poem, written during or immediately after the Holocaust, Jews rise as smoke after their bodies have burned, and disappear into the empty air where God resides.

I am inclined to read this as a sort of inverted negative theology. According to negative theology, God cannot be described, but can only be spoken of in terms of what God is not. In “Smoke,” however, God is said to dwell in the heavenly heights, and it is the Jewish people who disappear, who are in some important way impossible to locate. The poem ends, hauntingly, with a description of their absence—our absence—even in those places where a seemingly absent God is found.

The poem asks: what has the Holocaust done to the Jewish people? And answers: it has rendered them as incorporeal as God, it has effaced them from the earth so brutally that they are harder to identify even than God is.

I won’t attempt to comment on whether “Like a Trap” shows a progression in Glatstein’s theological thinking; I’ll leave that to his scholars and critics. But I find something sweet and melancholy, something so tender, in its description of a small, struggling American synagogue. There’s such intimacy in the rabbi’s writing a letter to God, and the fact that he sends it to “the old address” suggests that the old Jewish ways of connecting to God have not been totally destroyed, they’re still at least potentially accessible.

I love the mystery of this poem. Maybe God really does show up, for just a few minutes, in this uncrowded synagogue. I imagine that the synagogue will be closing soon, that its congregation is aging, its membership dwindling. Maybe I’m projecting, because certainly I’ve attended synagogues just like that, and often found them quite depressing. But the possibility remains, even or maybe especially in such a place, that God’s presence is real.

Certainly one could read the description of no one knowing whether God ever shows up as a condemnation of the synagogue’s worshippers, and their distance from the God they claim or maybe just pretend to serve. But I’d rather see it as a return to a kind of mystical negative theology: God’s presence is beyond all knowing, so how could they be certain whether God arrives? All they can do is tenderly invite God in, send God reminders to show up, and wonder whether God is ever there at all.

(Of course I’ve ignored this poem’s animating analogy, its title: the synagogue is like a trap. If you have thoughts about this I’d love to hear them.)

In “A Little Trap” the rage and visceral grief of “Smoke” are gone. But the Jewish people are not gone, not yet. Is God gone? Maybe, and maybe not. What is left is the question itself, the uncertainty, the intimacy of that wonder.

I love these two. So poignant

Re-reading Like a Trap after reading your reflections, I see what I couldn't at first: the possibility of setting a trap for God.