(Today’s post begins with some thoughts about the state of this newsletter. If you aren’t interested, please feel free to skip down to the poems!)

When I started this newsletter, over a year and a half ago, I was aimless and bewildered. I had just dropped out of a graduate program, and just quit a bad job adjuncting for a community college. I was reading a lot and writing a lot, and paying my bills through substitute teaching gigs for ESL teachers in the local public school system, which meant that I spent my days with kids from El Salvador, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Yemen, Cambodia, and so many other countries. I woke up most nights with the physical sensation that I was wasting my life. It felt as if I couldn’t lift a weight off from my chest. I was waiting for answers to that old question — “what do you want to be when you grow up?” — to reveal themselves.

And so, because I wanted to share what I was reading and writing and thinking about with other people, and to push my skills as a translator, and because Yiddish poetry was a consolation to me in that difficult time, I began this substack. I would translate poems for it on days I didn’t teach, which is how I was able to maintain that original pace of (at least) one new poem each week.

Much has changed since then. I’m not, mercifully, as aimless as I was; I have invigorating projects and commitments. All this means, though, that I can’t stick to the pace I once kept for this newsletter. So first of all, an apology, especially to those of you who became paying subscribers when I was sending poems and essays and hosting events more frequently than I am now: I’m sorry that the number of posts here has diminished.

And second of all, a request: Over the next month or two, I’ll be experimenting with new formats for and approaches to this newsletter. If you have suggestions or feedback about sustainable ways to keep sharing and celebrating Yiddish poetry and culture here, please don’t hesitate to let me know.

And third of all, gratitude: when I started this newsletter, I sent it to a couple dozen friends and family members I thought might be interested. I had no “platform,” no “following.” It’s hard for me to believe that these posts are now read by hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of people around the world. Thank you for being a part of this; your reading and your support mean a great deal to me.

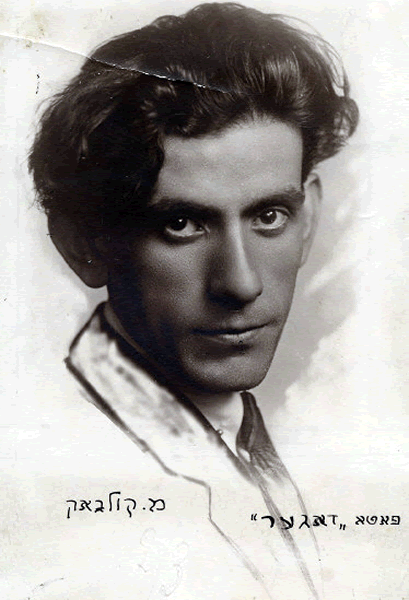

If you weren’t deterred by that wall of text, I’m excited to introduce a new poet today: Moyshe Kulbak. (Per contemporary conventions, I’m writing his name as Moyshe, although in his Lithuanian Yiddish dialect it would’ve been pronounced Meyshe.)

Another Yiddish poet with great hair.

Kulbak (1896-1937) was born in Smorgon, in what is now northeastern Belarus. The town’s wikipedia entry includes this tantalizing, contextless sentence, which raises many more questions than it answers: “Smorgon is known as the place where a school of bear training, the so-called ‘Bear Academy,’ was founded.”

It’ll be hard for me to stop wondering about this Bear Academy, but regardless: Kulbak received a traditional yeshiva education, and began to write Hebrew poetry during World War I. After the war, he moved first to Minsk and then to Vilna, where his first poetry collection was published in 1920 to great acclaim.

After a stint in Berlin, and several more years in Vilna, where he played an important role in that city’s Yiddish cultural scene, and became a beloved teacher in the local Yiddish gymnasium, Kulbak moved to Minsk in 1928. He continued writing, focusing especially on long poems, drama, and fiction, until September 1937, when he was arrested on false charges of espionage, one of many Minsk artists and intellectuals persecuted in a wave of Stalinist repression. After a month of imprisonment, Kulbak was executed on October 29.

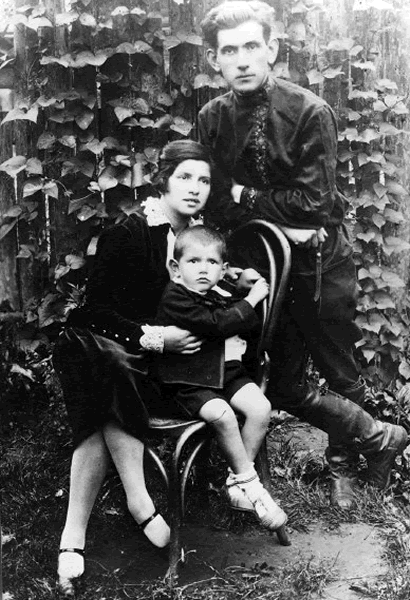

Kulbak with his wife, Zelda, and son Ilya -

photo courtesy of Eilat Gordin Levitan’s remarkable resource.

Though most of his work is still untranslated (except into Russian, after his official post-Stalin rehabilitation,) there are some great English editions of some of his fiction.

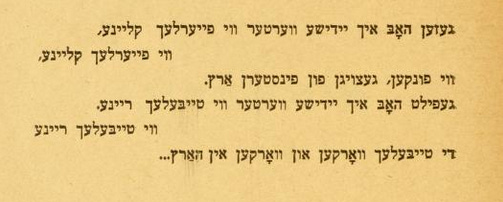

Both of the short poems below are taken from Shirim (Poems), his first book, published in Vilna in 1920.

[Untitled] I have seen Yiddish words like small flames, like small flames, like sparks, risen from dark ore. I have felt Yiddish words like white doves, like white doves. The doves coo and coo in my heart.

[Untitled] I walk around, around, around for a year, or two, or three, or it could be more: I turn up invited everywhere, everywhere, and everywhere is welter and waste... It's welter and waste, and desolate, and horribly boring, brrr! ...

The first of these two poems opens Kulbak’s debut poetry collection, functioning as a kind of epigraph. How moving, over a hundred years later, to think of the young poet, then in his early 20s, choosing these lines about the Yiddish language to introduce his work to an audience of Yiddish readers.

What is Yiddish here? It is elemental: its words are sparks and small flames, casting light and heat. It is also, therefore, dangerous. Yiddish has a real power, and if you’re not careful you can get burned. And Yiddish is an animal. There’s so much symbolism, of course, in the identification of Yiddish words with white doves, but I’m thinking beyond the obvious association of doves with peace, and with the story of Noah, to the fact that doves, unlike many species of bird, can be both wild and domesticated. Doesn’t that capture something about language, about poetry, about words themselves? These creatures at the border between wildness and domestication, tamed and untamed at once, capable of flight, singing in our bodies….

What to do, though, with this second poem, this odd piece of writing? My use of the phrase “welter and waste” here is a nod to Robert Alter, who uses it in his translation of the first line of Genesis, though it originates in Wallace Stevens’ “The Planet on the Table.” I chose this phrase in order to invoke what I see as Kulbak’s reference to a biblical, primordial state of desolation.

Wherever the poet goes, everything he finds is empy and inchoate. He wanders and wanders, and seems to find only an uncreated creation. I don’t quite know how to read this poem, but it reminds me of a comment I came across recently, in Claire Schwartz’s interview with Hélène Cixous. Schwartz says that “For [Edmond] Jabès, the word—a mark on the blank field of the page—distances us from the primordial nothingness of creation, but also touches the void by displacing the thing in the world to which it refers. Negating as it asserts, the word ceaselessly renews its relationship to nonexistence, becomes strange to itself.”

I had to read that out loud a few times to start to get a handle on it, but I take it to mean that language simultaneously erases and channels absence, emptiness, nothingness. Kulbak finds emptiness everywhere, and turns to language in order to make something real. But the words he finds, the poems he crafts, even as they create, still reenact the desolation whose place they take, whose emptiness they fill.

What’s with that brrr! at the poem’s end, though? Perhaps it’s the poet letting go of language in response to the desolation he finds, and reverting instead to a pre-verbal expression of embodied experience. Or maybe it’s just a young poet reveling in the newfound freedoms of post-World War I writing. If you have any thoughts about it, I would love to hear them.

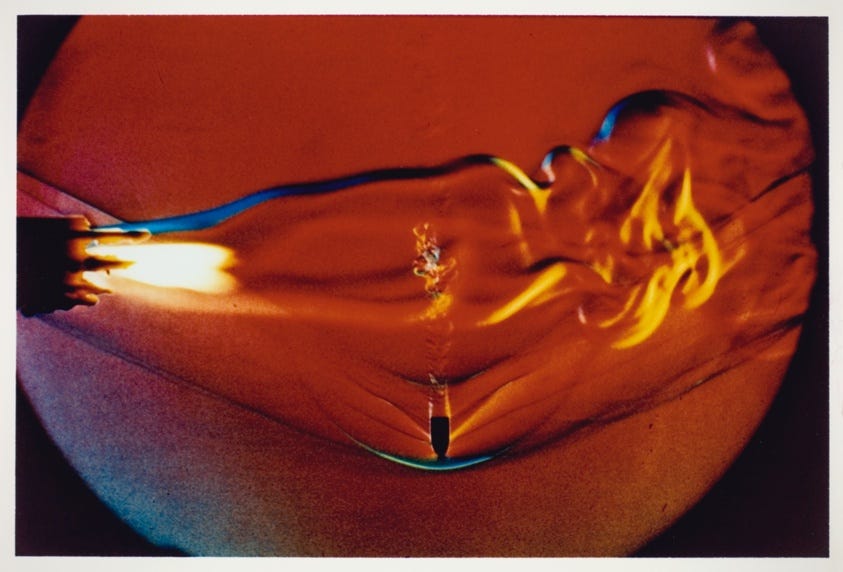

Today’s art pairing: Harold Edgerton’s 1973 “Bullet through Candle Flame”

The spark/flame imagery reminds me also of Alter's translation of Song of Solomon 8:6:

For strong as death is love,

fierce as Sheol is jealousy.

Its sparks are fiery sparks,

a fearsome flame.

A lot of his poetry and prose has been translated into Belarusian -- not only Russian. His writing reflects a lot of Jewish Belarusian reality of those times.