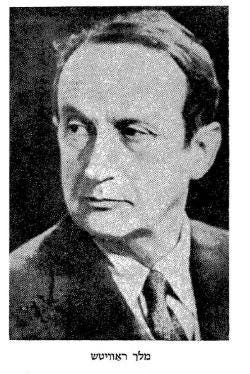

"Dear Sister, When I Die" by Melech Ravitch

After a rough bout of covid, I am back in action and excited to share some Yiddish poetry with you. Today we return to Melech Ravitch (1893-1976), who was one of the very first poets I translated here. I’ve returned to him twice since then, and I’m always glad to spend some time with his writing, which is surprisingly under-translated.

I often find myself taken by Ravitch’s melancholic mysticism, and by his idiosyncratic, sometimes anti-human relationship to animals and to the natural world, all of which is apparent in this poem and in the earlier ones I’ve shared.

I won’t repeat the biographical info from my previous posts about Ravitch, but this newsletter from the Yiddish Book Center has a nice tribute to his life and career.

So, without further ado, let’s dive right in! This poem was written in 1961, and was taken from Ravitch’s 1969 collection Iḳer shokhaḥti: lider un poemes fun di yorn 1954-1969 (Post Script: poems from the years 1954-1969).

Dear Sister, When I Die

Dear sister, when I die,

quietly following that final call,

wrap me in soft, green linen,

and give my body away to the flames.

I want to abandon my bones and sinews,

my whole form, like this,

through dark smoke to blue heights,

and to become like the blue sky.

Returning my body freely

at just this hour

will free the soul

to live again for an eternity.

And again, in the cycle of reincarnation,

again, prepared for a new return,

to become again a ring

within the rings of endlessness.

Yes, a ring within rings, again, again—

though not to return as a human, not that,

but a secret-filled deer in the forest,

an albatross by distant shores.

O, dear God, when I die,

I implore You, I curse, I bless,

incarnate me again thousands of times,

but never as a human.

You ask: why? You mean: do I want

to hide secrets from you now?

It's simple. God, the human is Your greatest

mistake, O You mistake-less God.

Dear sister, when I die,

quietly following that final call,

wrap me in soft, green linen,

and give my body away to the flames.Another elegiac, enchanting, death-haunted poem by Melech Ravitch. Death-haunted, I say, but also obsessed, through death, with life, and with life’s endless possibility.

This poem is really a prayer, both to a sister and to God. It’s worth noting how un-Jewish the poet’s request to his sister here is: cremation is traditionally prohibited in Judaism, and became even more taboo after the horrors of the Holocaust’s crematoria. The poet’s request that his body be burned places this poem in a distinctly unorthodox theological territory.

This unorthodoxy is even more striking in the context of a poem about the soul’s eternal life, since certain kabbalistic traditions maintain that someone who is voluntarily cremated has forfeited any future possibility of resurrection.

So the poem’s celebration of cremation is very clearly divergent from traditional Jewish belief. But what should we make of the paradoxical description we find here of an infallible God who has made a colossal mistake in creating humanity? From one perspective, this might seem like an almost heretical idea. But it puts me in mind of the flood narrative in Genesis, when a genocidal God resolves to wipe humanity out. Here’s Genesis 6:5-7:

The LORD saw how great was man’s wickedness on earth, and how every plan devised by his mind was nothing but evil all the time. And the LORD regretted that He had made man on earth, and His heart was saddened. The LORD said, “I will blot out from the earth the men whom I created—men together with beasts, creeping things, and birds of the sky; for I regret that I made them.”

How can it be heretical for a 20th-century poet to say that the creation of humanity was God’s terrible mistake, when God says the same thing in the most canonical text of them all?

If we read Ravitch’s rejection of humanness in the spirit of this Genesis passage, we still find one significant divergence: God, in the biblical narrative, decides to kill not just humanity, but the animal world in all its diversity as well. Ravitch does not go so far. For him, animals are the only creatures worth reincarnating as. The human being is a dead end, and having been a human once Ravitch wants never to be one again. But this stance on creation is actually more compassionate than God’s: both God and Ravitch see humanity as a mistake, but God alone includes the non-human world in his violent judgement.

Perhaps this is one way to understand Ravitch’s contradictory “I curse, I bless,” when he begs God to return him to life as an animal. He curses humanness, and blesses animality; he curses the life he has had, and blesses life itself.

The paradox of this poem, of course, is that it is a poem about (among other things) the desire to be incapable of poetry. Animals do not write poems. It is only because of the humanness the poet renounces that he can find a beautiful form to express that renunciation.

(By the way, does anyone reading this with more scholarly chops than me know if Ravitch had a sister? The YIVO encyclopedia mentions brothers, and though I haven’t done a very deep dive, none of the sources I looked at online refer to a sister. I’m wondering if this sister existed only in the world of poetry, or if she lived in Ravitch’s biography as well.)

Today’s art pairing: Gustave Courbet’s 1865 “The Deer” - “a secret-filled deer in the forest.”

I love this poem and your translation of it too, Daniel. I was wondering about the impersonal aspect of the Yiddish "a good sister," and then saw your question at the end. If he had a sister, he might have left off the "a" or he might indeed have written "tayere shvester," as you translated it, as a more intimate address? Maybe.

I think burning meant metaphorically, like extinction. I wonder if a different desire, even honest, in the past century, especially.