In Streets, by Anna Margolin

"Nevertheless, O God, O Torturer, I believe"

It’s been over a year since we looked at Anna Margolin’s (1887-1952) poetry, but my estimation of her only continues to grow. Once I would have said, like most Yiddish readers, that she was among the great Yiddish poets of the 20th century. Increasingly — and I don’t say this lightly — I think that she was among the great poets of the 20th century in any language, and I hope to spend more time reading her, and working to convince you of that claim.

I’ve written a little bit about Margolin already, discussing the misogyny with which she was received, the violent eroticism of her religious visions, and more, when I shared her Mary cycle of poems last summer.

(Margolin at 16, courtesy of Wikimedia commons)

If you’re just tuning in, however, here’s a biographical overview: Margolin was born Rosa Lebensboym in 1887, in what’s now the Belarusian city of Brest.

(Digression alert: I say “what’s now” because when Rosa Lebensboym was born there, Brest was in the Lithuania region of the Russian empire. The city changed hands a few times from World War I until 1921, when it became part of Poland until World War II, and then changed hands a few times again: Nazi Germany, the Red Army, Soviet Belarus, etc…. To complicate things further, Jews never called the city Brest. Its Yiddish name was Brisk, and it was known across the world as a center of rabbinic scholarship; traditional Jews still talk about the Brisker approach to Talmud study. When I worked for the Judaica division of Harvard’s library, a big part of my job was standardizing hundreds of years of bibliographic references, changing now-nonexistent places like “Brisk, Lithuania” in the library catalog to their modern names. It was fascinating, tedious work, charged with obscure and contentious histories!)

Lebensboym moved several times in childhood and adolescence, living in Odessa, Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), and Warsaw before moving to New York in 1906, where she joined that city’s Yiddish literary community and began writing poetry, fiction, and journalism for Yiddish newspapers like the anarchist daily Fraye Arbeter Shtime (Free Voice of Labor).

But Lebensboym didn’t seem to want settle down. She moved back to Europe, living in London, Paris, Warsaw again, and Tel Aviv, getting married and having a son, leaving her husband and son in Palestine, and returning to New York in 1913.

(The signed title page of Margolin’s only poetry collection.)

She used a number of pen names, but published all her poetry as Anna Margolin. All her poetry: just one book Lider (Poems), in 1929, plus scattered poems in newspapers and journals. And then she went silent. From 1932 until her death 20 years later Margolin lived as a recluse, suffering from poor mental and physical health, eventually never leaving her apartment.

But that one book of poems! What a book it is, what a mark it’s made, what a haunting presence it’s had on my consciousness. I’m excited to share another of Margolin’s poems today; it’s one I’ve returned to many times.

First, though, a brief reminder, and a piece of ephemera.

The reminder: the next Zoom discussion for paying subscribers will be this coming Tuesday, 8/29, at 7:00 pm EST. We’ll explore the ways that Yiddish poets presented and responded to American anti-black racism and white supremacy. How did Yiddish poets in America, mostly left-leaning immigrants from Europe, use their verse as a way of reacting against the racial violence they encountered here? It’ll be a fascinating program that I’m really looking forward to, and all paying subscribers will get a zoom link.

And the ephemera, to lighten the mood: a 1932 newspaper ad for the Tomche Tmimim Lubavitz Kosher Wurst Factory, Inc.

“Good news for American Orthodox Jewry,” the ad proclaims: “the students of the great Lubavitch Yeshiva ‘Tomchei Tmimim,’” a mystically-inclined rabbinical seminary, “have opened a wurst factory” on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Delicious! I love these small moments of cultural convergence. At last, if you found yourself lamenting the challenge of finding good sausage made by mystical rabbinical students, your day had come!

(Thanks to Eli Rubin for sharing this on twitter, or whatever twitter’s supposed to be called now.)

But without further ado, here’s Anna Margolin’s poem. It’s one of the first poems in her book, from the opening section, called “Roots.”

In Streets

Here a word of fear, and there a word full of regret.

Here I wept, and there I rested, suffering.

You have converted every street into Golgotha,

down every street my blood runs.

Here I wept. The walls dully

thundered a harsh decree against the weak and lost.

So many lords and ladies watched

the way a woman walked in tears, through twilight.

Was prayer and was fury, regret.

And now the last terror-filled note cries out

from life, sinking into the dust.

Nevertheless, O God, O Torturer, I believe:

with dying fingers I will lightly touch a star,

will hear an infinitely deep and caring word.

In the introduction to her bilingual Margolin collection, Drunk from the Bitter Truth, Shirley Kumove quotes from a letter that Margolin wrote: “I haven’t ever been able to be secular even though when I was very young I was a flaming anarchist. I have always talked to God, and in times of sorrow, I admit I have given God hell.”

It’s an illuminating passage: for Margolin, secularism isn’t an ideology, a value system, a philosophical claim about the world. It’s an impossibility! Some people talk about being unable to believe in God, regardless of how they try, but Margolin’s experience is the opposite: she can’t not believe, no matter how much she suffers, no matter how absurd or disquieting belief might be.

Margolin was not, by any means, an orthodox believer. She was less Moses, more Job, “giving God hell” when God deserved it. And in this poem we find an expression of her anguished, honest, ambivalently consoling faith.

“You have converted every street into Golgotha,” the poem’s speaker says. It’s an astonishing, horrifying image: every place is the archetypal site of the deepest pain and despair. It’s also a daring image for a Jewish poet writing in a Jewish language, appropriating Christian mythology in her search for the perfect metaphor. Or perhaps better to say reappropriating: according to Christian tradition, Golgotha is the location where Jesus was crucified, but the etymology comes from the Hebrew/Aramaic for skull.

Margolin’s bleak vision is of a world in which anywhere one goes is Golgotha, that place where the innocent suffer unto death. And, most daringly of all, it’s God’s fault. That, at least, is how I read the “You” in this line’s “You have converted,” since this poem contains no other second person addressee than God. This isn’t theology; Margolin isn’t theorizing about God, or recounting her experiences with divinity. No: this is anguished prayer, is fearless accusation, a new round in the human-divine wrestling match that begins in the book of Genesis.

You, God, Margolin is saying, have transformed all of life into the scene of infinite anguish. You are the supernal “Torturer.” When we consider the ways that Margolin suffered because of her physical and mental health, and when we consider the vast and petty suffering that takes place all around us and within us, every day, how can we fault her for saying this? It’s a striking illustration of the claim in her letter, that she has “given God hell.”

But the poem ends, somehow, in faith. “Nevertheless,” Margolin believes that her “dying fingers… will lightly touch a star,” that she will graze transcendence. Despite the endless despair God causes, she believes that “an infinitely deep and caring word” awaits her.

In this poem Margolin expresses a relationship to God that goes beyond categories of belief and disbelief, a faith profound enough to contain even its rejection. Like Job before her, Margolin’s refusal to deny the terrible reality of human suffering, and the role that any God must be playing in that pain, brings her to the brink of revelation. And also like Job, she expresses her anguished prayers and accusations in beautiful, enduring poetry.

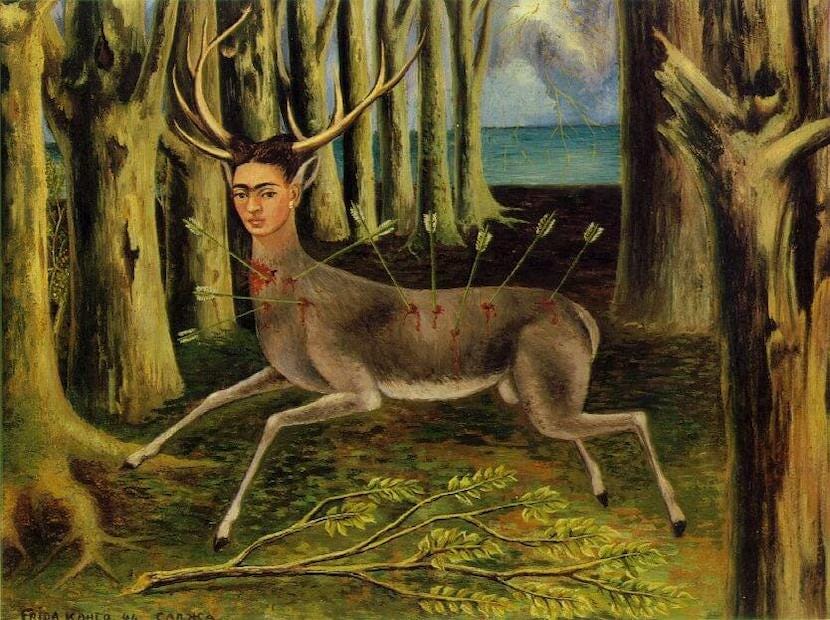

Today’s art pairing: Frida Kahlo’s 1946 “The Wounded Deer.” I don’t have the clearest articulation of why this painting jumped out at me as a partner to this poem, except to say that they are both honest, idiosyncratic expressions of suffering, and of the ways that suffering can find a form in mysterious, transcendent beauty. Just as for Margolin the reality of suffering transforms the whole world into Golgotha, I have the sense seeing this painting that for Kahlo, the whole world is a hunting ground, and every human is, in potential or in actuality, God’s prey.

Incredible, Danny!