Mary, Continued

More from Anna Margolin's series

By popular demand, I’m continuing Anna Margolin’s Mary cycle this week, with the next two poems in that sequence out of the total seven. If you missed the first two poems in this cycle, you can find them here; if you’d like to read the biographical outline from when I first introduced Margolin in May, you can click through to this link. I love Margolin's Mary poems, and I've been gratified to learn from your responses that many of you do too. They're very recognizable to me, as if they issue from a voice I know as well as my own, and at the same time so strange, so alien.

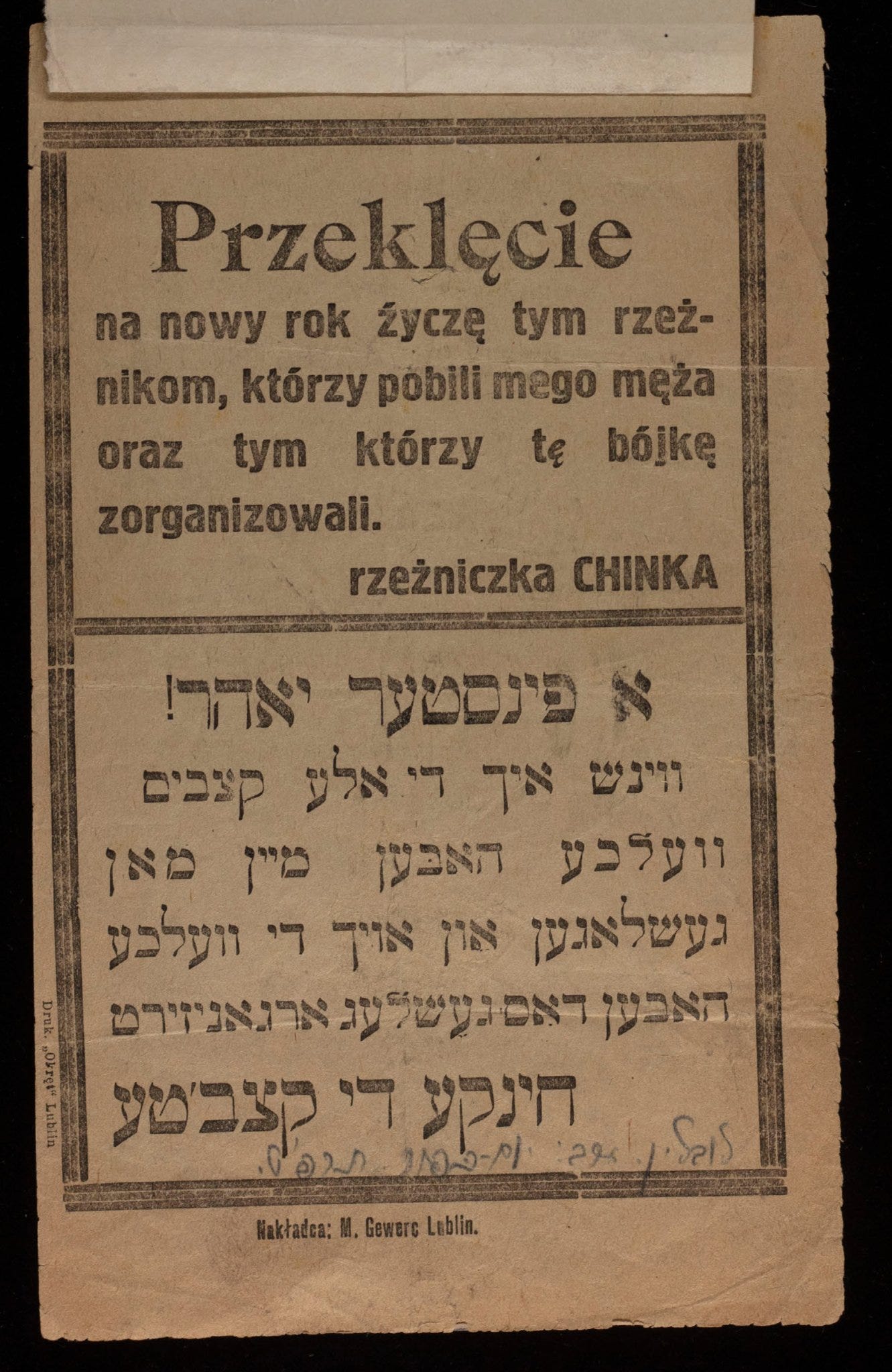

Since I’ve already shared some context around Margolin’s life and work, I thought I’d start things off this week with something completely different, and a bit digressive: a curious piece of Yiddish ephemera, shared by a Yiddishist in Lublin, Poland, with whom I’ve corresponded a little bit online.

This leaflet is dated from the Eve of Yom Kippur, 1928. I can’t read Polish, but the Yiddish says: “A Dark Year I wish upon all the butchers who attacked my husband, and upon those who organized the attack.” It’s signed by “Khinke the butcher.” Apparently Khinke and her husband were butchers engaged in a long-standing business dispute with an organization of wholesale butchers. It seems that this dispute turned violent, and Khinke distributed these leaflets at synagogues across the city of Lublin during the High Holidays.

I won’t spend too many words on this digression, but wanted to share because it seemed to me an interesting relic of a now long-gone Yiddish world, a piece of paper that is at once relatively mundane and full of an overwhelming pathos. Archives are strange places, and often these fragments of historic lives raise so many more questions than they answer.

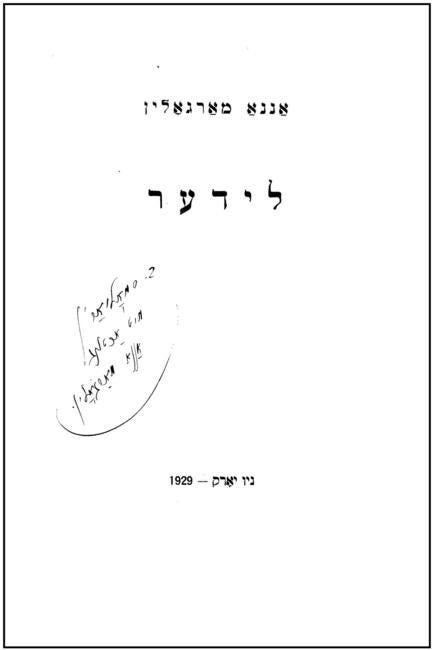

Anyway, today’s poems—numbers 3 and 4 of Margolin’s Mary sequence—are below, taken from her 1929 Lider. Here’s the title page of that book, with Margolin’s signature:

Mary and the Priest

Mary, you are a glass of sacramental wine,

a delicately shaped glass of wine

on a ruined altar.

A priest

with slow and slender hands

lifts high the crystal glass.

And your life burns and quivers

in his eyes, in his hands,

and wants—in an intense, ecstatic joy—

to be shattered.

Mary, Mary,

soon with a soft cry

your life will be broken,

and your death will paint

a dead stone

hot and red.

Forgotten gods will smile,

hot and red.

Lonely Mary Among people she is as if within a wilderness, whispering her name to herself: “Mary.” And Mary was, and also her beloved man: “as if through a warm fog, Mary, I hear your voice, I see your shadow,” she whispered sometimes under her breath. And leafing tenderly through an invented happiness, and suddenly becoming pale in self-loathing.

The ending of “Lonely Mary” is shockingly abrupt each time I read it, in a way that’s devastating: I feel as if Margolin has thrown me off a cliff, and denied me any landing place. Mary becomes pale in self-loathing—and then what? Then: nothing. We’re left with that image’s brutal power.

And “Mary and the Priest” is charged with a disturbing, annihilating eroticism. In my reading, Mary is a sacrificial victim who is desperate to be sacrificed. Her “life… wants—in an intense, ecstatic joy— / to be shattered” by the priest who holds her in his hands.

(Heads up: this is about to get kind of weird.)

This poem makes me think of the 20th century French philosopher Georges Bataille. He was obsessed with human sacrifice, and in 1932 started a secret society about which not too much is known. Scholar Allan Stoekl writes that the society’s aspirations “were the rebirth of myth and the touching off in society of an explosion of the primitive communal drives leading to sacrifice.”

Wikipedia puts it a little more ominously, with an understatement I find absurd: “members [of the secret society] discussed carrying out a human sacrifice, but this may never have been carried out.” A lot hinges on the force of that “may never,” and other sources say that Batailles himself wanted to be the society’s sacrificial victim, but none of his comrades agreed to decapitate him.

This is all a long-winded way of getting to my main point: that Batailles’ thought, in which human sacrifice was central, and Margolin’s “Mary and the Priest,” based around Mary as a sanctified glass of wine eager to be broken and thereby sacrificed, express similar ideas.

Consider the intense ecstasy of Mary’s desire to be shattered, alongside Batailles’ definition of the sacred as “a prodigious effervescence of life that, for the sake of duration, the order of things holds in check, and that this holding changes into a breaking loose, that is, into violence.” As the writer Danelle Gallo explains this, commenting on Batailles, “an experience of the sacred occurs through a violent rupture of boundaries that releases one into a state of simultaneous ecstasy and anguish.”

That seems to me connected to Mary’s yearning to be shattered: she desires connection with the sacred, even though (or maybe precisely because) what is truly sacred can only be accessed through self-destruction.

Batailles’ definition of eroticism is not at all different from his understanding of sacrifice, and this, too, seems resonant with Margolin’s Mary. In the book Eroticism, Batailles writes that “the whole business of eroticism is to destroy the self-contained character of the participators as they are in their normal lives.”

Mary as a glass of wine, about to be shattered, is a striking image for the destruction of “a self-contained character.” And the poem’s deeply unsettling conclusion, that Mary’s sacrificial death will make “forgotten gods… smile / hot and red,” evokes Batailles’ idea that human sacrifice enables people to access the subconscious, essential, and overwhelmingly powerful forces that our civilization has sought to submerge.

I’m going to stop here before this gets too weird, and certainly I’ve only scratched the surface of what I find resonant between Batailles and Margolin, and of everything to unpack in these poems. I should also add that my wife thinks I’m misreading this poem completely by focusing too much on a too-literal idea of sacrifice, and maybe she’s correct. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

But I’m left wondering whether Mary’s loneliness in the second of today’s poems, and her sacrificial eroticism in the first, are really two sides of the same coin. That description of her “as if within a wilderness,” alone, when she is with others, is deeply moving to me. Perhaps it’s that sense of alienation that makes her yearn so deeply to be violently subsumed into the sacred. Margolin has given us an astonishing and subversive rereading of Christian writing about Mary, but it’s a rereading that strikes me as very honest, and very human.

“Among people she is

as if within a wilderness,

whispering her name

to herself: “

What a tremendous couple of poems! Thank you for your (not at all weird) thoughts on sacrifice and all the shades of meaning in these. Much to ponder!