Mary

by Anna Margolin

Thanks, everyone, for your patience through this summer’s hiatus. I’m happy to get back to this newsletter.

My hope had been to send this next installment out two weeks ago, but I’ve been pretty sick for the past ten-ish days, and not able to do much writing or thinking. Instead, I’ve spent most of my time reading mystery novels and for some reason listening, over and over again, to Boulder to Birmingham, Emmylou Harris’s beautiful elegy for Gram Parsons.

So I’m grateful to return here, with another installment of poetry by Anna Margolin. I introduced her biography, along with her epitaph and the poem “Full of Night and Tears,” a few weeks ago. But I’ve worried since then that I focused overwhelmingly on presenting Margolin as a tragic figure, that I offered—to borrow a phrase from the great Jewish historian Salo Baron—a too lachrymose conception of her work, her life.

I wanted, with today’s installment, to complicate that a little bit. To share some of what I see as her tremendous spiritual depth, which comes from an ability to join the transcendent and the prosaic together within a stance of profound, relatable, almost unbearable yearning.

Below are the first two poems from her “Mary” cycle, published (like pretty much all her work) in 1929’s Lider.

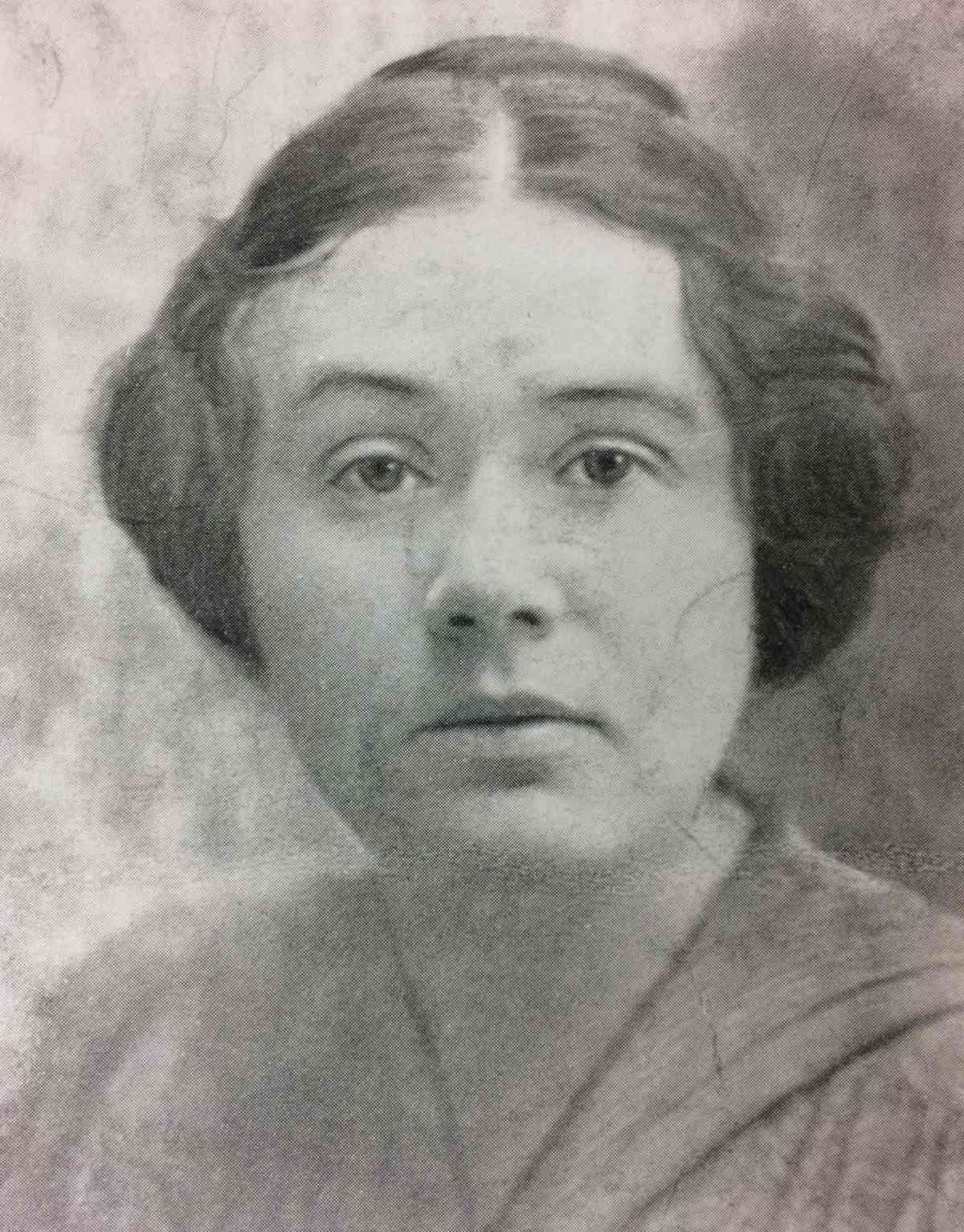

Margolin, courtesy of the YIVO archives.

What Do You Want, Mary?

What do you want, Mary?

Perhaps a child to doze, illuminated, in my lap.

What do you want, Mary?

Deep silent evenings in the house

alone and slowly wandering,

waiting, always waiting.

And let my love be for a man who does not love me,

as quiet and as vast as desperation.

What do you want, Mary?

I would have wanted my feet to take root in the earth,

to stand alone within a dew-lit field.

The sun moves through me as through a young world,

through the ripeness and smell of the sleeping pasture.

Suddenly wide and wild rain descends

and beats and kisses me, loud and hard,

a storm like an eagle:

it sinks into me, screaming, it bends me everywhere.

Am I a person? Am I lightning, the road’s unrest,

the black and sighing earth?

I don’t know anymore. With tearful eyes

I surrender myself to the sun, the wind, the rain.

But what do you want, Mary?Mary’s Prayer God, humble and silent are the ways. Through the fires of sin and through tears the ways all lead to you. I have built out of love a nest for you, and out of silence a temple. I am your watchman, your servant, your lover, and I have never seen your face. I lie at the edge of the world and you move through me, dark as the hour of death. You move like a broadsword, gleaming.

If there’s interest, I’ll send out more from this series of “Mary” poems.

Much scholarship has been written about Margolin’s use of Mary as a poetic persona here, and how this both participates in and subverts the Yiddish modernist project of (re)appropriating the figure of Jesus as an emblem of Jewish creativity. (If this is of further interest, you can check out Melissa Weininger’s article on the subject.)

But rather than focus on a scholarly argument, I’d like to try to think aloud a little bit about why the end of “What Do You Want, Mary?” moves me so much.

“Am I a person?” Margolin’s Mary asks. “Am I lightning, the road’s unrest, / the black and sighing earth? / I don’t know anymore.” It give me chills each time I read it.

Maybe because I find something recognizable about these questions. Who, after all, am I? What is this thing called a person, and what is this particular person that I might be? We’ve all asked versions of this to ourselves, and—if you’re like me—have sometimes pushed the questions away because they feel unanswerable, and terrifying in their unanswerability.

At the same time these questions are very strange to me. I have asked myself who and what I am, it’s true, but I’ve never continued by wondering whether I am “lighting, the road’s unrest, the black and sighing earth.” Margolin’s confidence, and the simplicity of her language, make these seem like natural and even obvious follow-ups, so that when I read this I find myself wondering right alongside her whether I am lightning after all, and even wondering why I never thought to ask this before.

The questions are at once strange and recognizable, and that’s so much of why I turn to art: to encounter what is recognizable in what is stranger than I could have imagined, and to encounter which is unspeakably alien in what I’ve always thought I knew.

Of course, I haven’t talked at all about the fact that the poems are written through the persona of Mary, which only magnifies their strangeness and their power. Mary who, according to Marina Werner,1 is “the one creature in whom all opposites are reconciled…. Christ the God-Man and Mary the Virgin-Mother blot out antinomy, absolve contradiction, and manifest that the impossible is possible with God.”

But I don’t think this describes Margolin’s Mary. Margolin’s Mary, the Mary of these poems, is a creature in whom opposites reject reconciliation. That closing repetition, “But what do you want, Mary?” is the ultimate irresolution; what a bold move it is to end the poem on a line that so demands, and so refuses, an answer.

(A question, then: if, as I read it, Mary is this poem’s speaker, then who is asking these questions? I’m inclined to say that it is also Mary, in conversation with herself.)

What Margolin has done here is take the grand, mythological Mary and transpose her into a human figure, one we can each recognize in ourselves. Or perhaps as a braver, more honest version of ourselves, because we—because I, I mean—habitually run from the questions that Margolin’s Mary asks and answers as well as she can, even when no answer is possible. She doesn’t evade the questions that come from and constitute her life.

As always, there’s so much more I’d like to say here, and I wish I had the time and space to comment on “Mary’s Prayer” as well. I’ve been thinking about the moment in this poem where Mary tells God, “I have never seen your face,” in comparison with Exodus 33:11, where we’re told that God would speak with Moses “face to face, as one person speaks to another,” a comparison which the poem invites. But I’m not sure what to do to with it.

God’s face is unknowable even to Mary, with whom God has—according to Christian tradition—conceived a son. But Margolin, as a Jewish writer, subverts any orthodox version of that Christian statement. Maybe God is unknowable especially to Mary. Or maybe God is equally unknowable to her as to the rest of us, but she feels it with an exceptionally visceral anguish.

Your thoughts are welcome, of course, in comments or by email. I’m glad to get back to the routine of this newsletter, and I’ll see you again next week.

Thanks to the Weininger article I linked to above for highlighting this helpful quote.

Hi Daniel,

I just wanted to say that I really love your Substack. I started learning Yiddish last year, and your issues are giving me the opportunity to learn more about Yiddish writers and engage with their work in a different way. Thank you!

Boulder to Birmingham 👏