After a long hiatus, I’m delighted to return with more Yiddish poetry in translation. Thanks to everyone who’s been a long-time reader, and thanks as well to everyone who’s new here.

Since I last posted , I’ve had some big changes: I now work full-time as the program manager for Yetzirah, the only national literary non-profit dedicated to supporting Jewish poets and Jewish poetry, an organization you might, if you’re a reader here, be interested in following or supporting. I’m glad to say that I’ve recovered from the bout of covid that stopped me in my tracks about 14 months ago. And, not to bury the lede too much, but I’ve become the father of a perfect baby boy.

Amidst all those personal transitions, as the world continues to burn, it seemed like the right time to dive back into sharing Yiddish poems. I’ve missed putting these translations and comments together, and I’ve missed the conversations they invited. I started this post by saying thank you, and I really meant it: your reading this newsletter means a great deal to me.

So, without further ado, here’s a strange and timely poem by Melech Ravitch, whom I’ve shared and discussed a number of times before. Since you can find biographical info about Ravitch in those posts if you’re interested, let’s get straight to the poem, which was written in 1934; the Yiddish below comes from Ravitch’s career retrospective Lider fun Mayne Lider, published in Montreal in 1954.

Inside New York’s Statue of Liberty I am a man of flesh and blood and bone, my soul is love, laughter, and tears — and you? Woman, empty iron giant, with a torch raised in your hand, you are a golem-woman with tin skin mounted upon a skeleton of steel — — your tin lips have never kissed bread. Your iron ribs have never rocked a man in bed, and — — I love you with a young love, fiery and tender, for thirty years of youth and manhood I have yearned for you, awaiting your first glance. I am a poet, a wanderer, a Jew, the steps to my soul are my poem's shaky stanzas and the steps to yours — unique among a million minds— to your head, to your consciousness— a hundred iron steps. Hollow is your soul, cold in winter, hot in summer, as in every structure made of tin. Of course it is so wondrous and magnificent to wander through your soul's steps with hundreds of others, to grow weary, to sing within you a glowing and human-pulsing love song, to you! — Whose veins of steel and wire circulate electric light instead of blood, because you are only a golem, monument to freedom — symbol — — and because you are a golem, symbol, freedom's monument, I write this love poem with hands that tremble in youth's fervor, with gleaming eyes, with simmering blood, and please believe me, woman, if I pressed my lips against your tin walls, and against the proud walls of your throat — and kissed them secretly, so that no one would see and say: perhaps he is a poet, and is totally disturbed — — that love would flow out of the purest heart, and this poor, earnest poem is a love poem, because never before have I known love like this, no other woman has ever been like you — like freedom — whose symbol you, once and for all eternity, have claimed the right to be. Your torch aims toward New York — but your light burns in every region of the world. Some bless you and some curse you, some esteem you and some detest you, some revere you and some mock you, and I — I have a simple love and faith. Because curses and hatred are just wind, just dust. — Oh, it is true, you lady, you freedom, today you are a fallen woman, and perhaps — perhaps because of this my love for you is so tender and deep — in your tin belly, you tin symbol, you are pregnant with the new redeemer of all worlds — they may laugh at you, they may curse you, you, but you will birth that new redeemer in light and faith, you will raise him in your hands — your son — as you raise your torch today, over all men. — And those who are weeping will laugh, and those who now curse will weep. United, guided by a child, freedom, beloved, yours, only yours, only your son will be the world's redeemer; a son of the spirit of all who are in love with you! Oh, may the breath of this love poem — conceived in love for you — be one part of the spirit that will fill your womb.

I love this poem’s ambivalence and strange eroticism.

It’s worth noting, perhaps, that Ravitch never lived for long in the United States: he spent some time in New York City in the late 1930s, when he was also moving between Mexico, Argentina, Australia, and elsewhere after leaving his native Europe, before he settled permanently in Montreal in 1941.

So what is the Statue of Liberty here, to this poet who chose never to become an American? It is a contradiction: the ultimate symbol of freedom, alive with electricity and worthy of devotion, and at the same time an empty monument, a vacuous and hollow ideal, waiting for a messianic future. Above all, the Statue is a golem: animate and inanimate at once, a mass of raw materials brought magically to life by the power of human faith and creativity, both monstrous and potentially capable of protecting the most vulnerable in its midst.

But Ravitch’s Statue of Liberty is not just any golem. She is a golem Virgin Mary: a spirit will impregnate the Statue, “the spirit of all who are in love with you,” and the son she bears will redeem the world.

The poem ends with a prayer that this poem itself might be part of the force with which the Statue conceives her son. It’s a daring and beautiful move: if the Statue is a kind of Virgin Mary, then the Jewish refugee poet wants to become a kind of God, whose holy spirit can impregnate a statue of iron and tin and bloodless electricity, ushering in a messianic era of unity and freedom.

I’m curious how you read the tone of this poem, which is hard for me to pin down. Ravitch is skeptical of the American democratic project and its symbolism, even as he holds onto belief in that symbolism’s redemptive power.

This is a much more ambivalent poetic vision of the Statue of Liberty than the best-known one, by another Jewish poet. For Lazarus, the God-like Statue embraces “the huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” while for Ravitch, the hollow statue awaits the God-like power of those same huddled masses, whose erotic love of freedom is necessary to bring her empty ideal into reality.

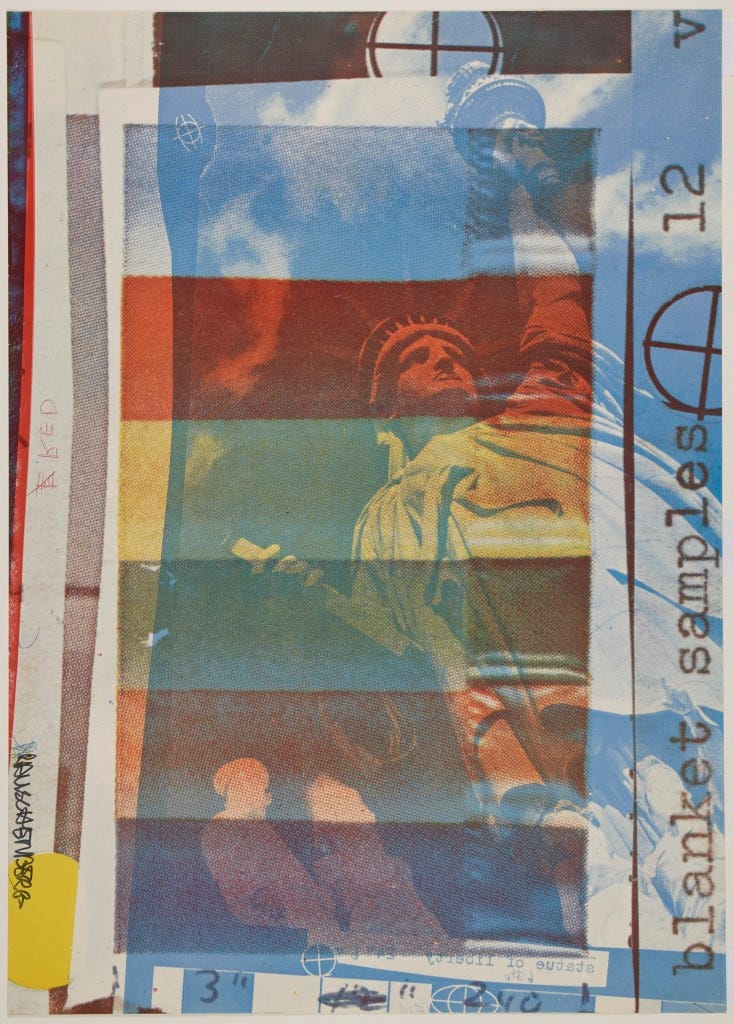

Robert Rauschenberg’s 1963 lithograph, Statue of Liberty:

Welcome back and mazel Tov on the birth of your child! I have missed your selections and interpretations. This is a beautiful poem. I think it's perfect for our time, embodying a guarded hope that someone conceived in freedom will change the world. We need it. This poem tells me that any of us (all of us?) with passion strong enough could help to bring that to be.

This poem is a bridge from Whitman to the Beat poets, like Ginsberg. A very interesting piece.