As the holiday closes, I’m wishing a freilichn Chanukah - happy Chanukah - to all my readers! Thanks for being a part of this.

Today we’ll look at another poem by Jacob Glatstein, whom I’ve written about a number of times, and whose 1961 poetry collection provides this newsletter’s name. I won’t repeat his biography here - you can find its outlines in the first post I wrote about him, now a year and a half ago - but I did want to share a brief anecdote from Ruth Whitman’s introduction to her 1972 Selected Poems of Jacob Glatstein, which is out of print. This story features Glatstein alongside some of the other Yiddish poetry personalities we’ve come to know here.

One afternoon, [Glatstein] came into the cafeteria [on East Broadway, where Yiddish writers liked to hang out] and found the poet Anna Margolin and the poet-critic Noah Steinberg having an argument. Anna Margolin, a woman with a very free life style, had a “deliciously cruel” manner of caressing the hand of her victim while she told him killing truths about his work. Steinberg had just published some poems in… a socialist paper. Margolin, stroking his hand, was telling him how terrible the poems were. She called Glatstein over to their table and asked him if he didn’t think Steinberg’s poems were garbage. Glatstein, embarrassed, said, “well, I wouldn’t call it great poetry.” Anna said to Steinberg, “see, Glatstein doesn’t like it either.” And Steinberg retorted, “Yes, I can take it from Glatstein, but who are you to criticize me?” Anna stopped caressing his hand, and taking up her unfinished glass of tea, tossed it in his face. Without a word he lifted the pitcher of water from the table and poured it over her head. Some of the warm tea fell on one leg of Glatstein’s trousers, while the cold water from the pitcher wet his other leg.

Reuven Iceland, Anna’s lover, was working nearby…. She called him to her rescue. He burst into the cafe, threatening to kill Steinberg. Steinberg, a very large man, took the threat calmly. He said, “I wouldn’t start a fight if I were you—I could kill ten like you.” Iceland was startled. “How can you do that?” he asked. “Because I eat carrots every day.” And Steinberg pulled a carrot out of his pocket and started munching it. He offered a carrot to Iceland, who took it as a pledge of peace, and the four poets sat down to eat and drink together.

The high drama of Yiddish writers! Insults, violence, a Popeye-like commitment to the masculinity of vegetables…. But note Steinberg’s response to Margolin’s criticisms: “Yes, I can take it from Glatstein, but who are you to criticize me?” Surely a deep misogyny underlies this comment. But it also speaks to the tremendous esteem with which the Yiddish literary world saw Glatstein, even from a relatively young age.

On a different note, before we get into today’s poem, here’s a bit of recent Yiddish music - from Yossi Desser’s “Yiddish Chanukah Carols” album - to help you stay in the holiday spirit.

The poem below is taken from Glatstein’s 1953 collection, Dem Tatns Shotn (Father’s Shadow.)

Revelation God is revealed to us in an intelligible frame. In the benevolence of nourished sheep, in the goodness of a Eugene Debs, in the lightning flash of an unexpected rhyme. God finds His frame. I write these aphorisms down and sing them like a pious liturgy until I sense their meaning, their taste. God is revealed to us in a golden frame. Evening slashes with the chill of steel and mines through night as if it were black earth. Before my eyes a valley of darkness is plowed by glowing threads. The sky clouds over with dozing hens. Fireflies quickly flash codes. I see it all through the eyes of a grateful pagan. I am quiet. A niggun purifies within me: Everything depends on you. On the goodness of your chilly hands. I go, and an echo of footsteps escorts me. My own voice is unheard. At a crossroads, I say: Here I will dream into the day. I lie down and listen. It's too dark even for a revelation. Perhaps I'll hear a divine rustling, through the night and my fear. A voice calls from a vacant window. Come home. Hurry. I wait. Don't be late. The loyal voice quivers. God finds his frame. A lamp like a bright bell slashes the darkness.

I referred to this as “a poem for Chanukah,” even though it has nothing explicit to do with the holiday. What I had in mind was this poem’s theme of revelation in a time and place of darkness, a time and place in which revelation seems as distant and impossible as spring does in the depths of winter. I think of this as the exact theme of Chanukah. “It’s too dark even for a revelation,” Glatstein writes. And yet, nevertheless, God is revealed. “Perhaps I’ll hear a divine rustling, / through the night and my fear.” I love that word, “rustling,” to describe the sudden and unexpected and impossible presence of divinity, of transcendent illumination, despite and within illumination’s absurdity. It suggests to me a tiny sound, easy to miss, the scarcest stirring of motion, the kind of thing we might ignore if we notice it at all.

But isn’t that what art can do—can allow us to see and to feel the minuscule revelations we would otherwise pass by, or dismiss as inconsequential? And isn’t that the miracle we’ve been reenacting on Chanukah—the idea that the frailest light source against the most overwhelming darkness can, irrationally and literally incredibly, cast an infinite brightness?

God is revealed, according to this poem, in the friendliness of cared-for sheep, in the craftsmanship and beauty of poetry, and in the benevolence of important American socialist Eugene Debs. (Fun piece of trivia: the call sign for The Forward’s Yiddish radio station, WEVD, was named in memory of Debs.) I love that this poem offers such different possible arenas for revelation: God can be found in animality, in art, in politics; God is not limited to one area, to grandeur, or to what we habitually and reductively refer to as “religion.” “A voice calls from a vacant window.” Even from what seems to be abject emptiness, revelation can be found.

Of course, the world is a pretty dark place. This is true around the winter solstice, and it’s true in times of war, and it’s true in general; all you have to do is look around. Darkness is everywhere.

But so is light. “Glowing threads” plow the pitch-black valley. The darkness, with all its fear and despair and loneliness, is still real. But somehow, through art and through ritual, we can find those little scraps of light, as Glatstein describes in this poem. And even if they’re not enough, miraculously, for just a moment, they can be enough. That’s the miracle of Chanukah, and I hope that we can all continue to find some glimpses of a light to slash the darkness when everything looks bleak.

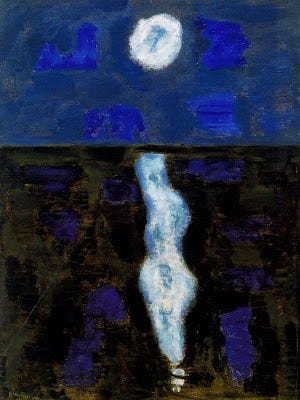

Today’s art pairing: Milton Avery’s 1957 “White Moon”