Today I’m excited to introduce you to a poet we haven’t read here before: Dovid Hofshteyn (1889-1952), one of the great Soviet Yiddish modernists.

Hofshteyn was born near Kyiv, Ukraine, and came from a family of artists. He was descended from Pedotser, the stage name of Aron-Moyshe Kholodenko, a violinist and composer who was one of the 19th century’s great klezmer virtuosos; his younger sister, Shifre Kholodenko, was also a renowned poet and translator; his cousin Osher Shvartsman, was a highly influential modernist Yiddish poet, particularly known for his war poetry, and became a Soviet icon after dying as a hero in the Red Army, in 1919.

Hofshteyn himself had a complicated relationship to the communist regime. He supported it at first, moving to Moscow in 1920, writing for the communist Yiddish press and leading the realist Yiddish theater movement. But in 1924, Hofshteyn — who had been educated in Russian and Hebrew — publicly called for the teaching of Hebrew in Russia. Hebrew had no place in Soviet ideology, and after being what we might anachronistically call “cancelled,” Hofshteyn moved to Palestine for several years, struggling for work there, before returning to Kyiv.

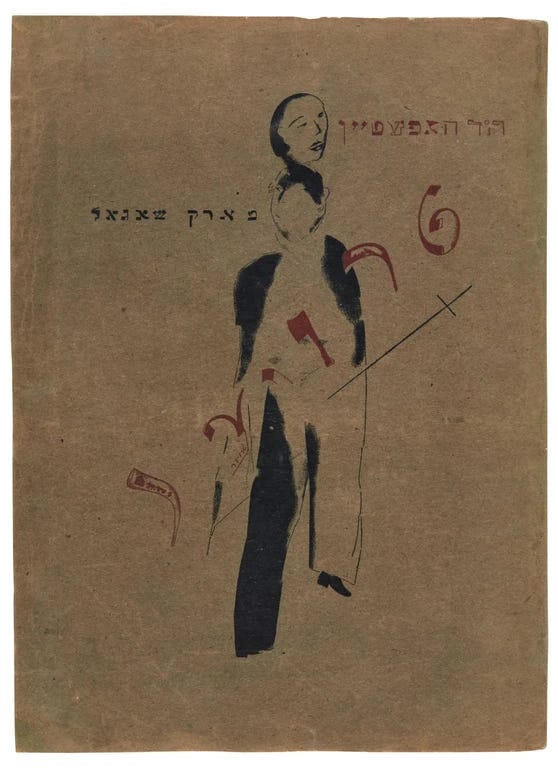

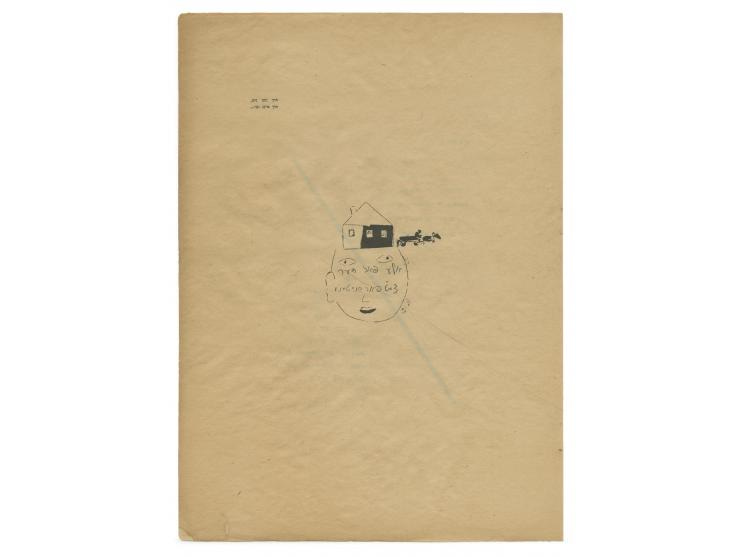

Along the way, Hofshteyn had befriended many leading Yiddish artists, like Marc Chagall. I mention this so I can share these cool illustrations Chagall did for Hofshteyn’s 1922 poetry collection Troyer (Sadness):

Despite his pro-Hebrew heresy, Hofshteyn rose through the ranks of the Soviet cultural world: he represented Yiddish in the Ukrainian Writers’ Union, and in 1940 became an official member of the communist party.

It didn’t last long. Astute readers might have noticed that death year, 1952, and connected it to the other Yiddish poets we’ve discussed here who also died then. Hofshteyn too was executed on August 12, 1952, one of the victims of the so-called Night of the Murdered Poets, killed in Stalin’s post-war purge of Jewish cultural leaders. He was arrested four years earlier, in September, 1948—not long after he had sent a telegram to Golda Meir, “about the need to revive Hebrew in the USSR.”1

I keep thinking about this telegram, and everything it represented. 24 years after losing his livelihood because of a countercultural, dissident commitment to the Hebrew language, and while Stalin’s repressions were only increasing, Hofshteyn refused to surrender his allegiance to the oldest and most universal language of the Jewish people. He wasn’t stupid, of course. He had to know what he was risking. But some things—a culture, a language and everything it contains—he must have thought worth dying for.

Today’s poem was written in 1944—I took the Yiddish from Hofshteyn’s collection Ikh Gloyb (I Believe), published in New York in 1945.

Ukraine

From smoke, from rupture, from ash, from shame,

I see: you raise your mangled hand,

your blood-coated head rises,

I can see your countenance! Oh, it lives, it lives.

Your gaze, still childish, now shows a mother's pain,

and the joy that follows danger shines,

the understanding that follows bewilderment,

like water in spring, from underneath ice—

I see: your body rises up, your form,

on which your torn clothes barely hang,

and the filthy rags fall from your frame—

you're visible, a grown child, a wife,

a body bright with beauty, gleaming

through shame, through derision, through the foe's violence.

It's a young and sure and unadulterated strength

that still becomes, that purifies without end, and laughs,

and soon will heal the agony, the shame—

It's Ukraine, my home,

Ukraine, my nation. The last two newsletters I sent out were responses to war, to trauma, to catastrophe. I was looking for poetry that could feel adequate to this terrible moment of violence in Israel and Gaza, and I found it in poetic responses to the Holocaust.

But the Middle East is not the only place where civilians are being attacked, even though the headlines have largely shifted away from Ukraine. It struck me how little attention was being paid to that terrible, ongoing war, especially after October 7, and I started thinking about what Yiddish poems might be meaningful responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Since so many great Yiddish poets were Ukrainian, and last year was not the first time, of course, that Ukraine has been brutally attacked by a neighboring country, it was not so hard to find a poem that was explicitly suited to this moment.

This poem for Ukraine, by Dovid Hofshteyn, written for a very different war, has apparently become a popular piece of cultural resistance. It’s easy to see why: the poem begins in the wartime degradation of smoke and ash and shame. That first line is about as desolate as it gets. But up from that despair, the bloody visage of the nation rises, “bright with beauty,” ready to heal itself.

In general, as a matter of both principle and aesthetic instinct, I’m not a big fan of nationalism: it tends to lead to destructive politics and cliched art. Nevertheless, I find this poem moving, even inspiring. Its repetitions of “I see” ground us in the poem’s tactile imagery, forcing us away from the abstractions into which many nationalist poems with similar themes fall away.

There’s one particular moment, lost in translation, that I love most of all here. The original poem is written in loose rhymes, and towards the end, Hofshteyn gives us the almost-rhyme of קראַפֿט, kraft, power or strength, with לאַכט, lakht, laughs. If a rhyme is a kind of implicit argument of kinship between two words or two ideas, then Hofshteyn is subtly suggesting here that a deep relationship exists between laughter and power, that laughter is a form of strength, even against the most destructive violence.

Today’s art pairing: Untitled, a 1941 painting by the Ukrainian-American Janet Sobel

https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/hofshteyn_dovid

Love the Kraft/lacht rhyme.