Ashes and Language

Two Poems by Jacob Glatstein, and an upcoming subscriber event

In June I sent out a short series of Jacob Glatsteins’s (1896-1971) poems, which you can find here, here, and here. Since this Substack borrows its name from his 1961 poetry collection, Di Freyd Fun Yidishn Vort, and since his poetry is phenomenal, it seems fitting to return to his work, and I’m excited to share two more poems by Glatstein, both from that 1961 book.

I’ve written about Glatstein’s life and biography before, and unlike some of the lesser-known writers I’ve shared you can learn much about him on the internet, so I won’t repeat myself here. You might find interesting, however, this short video of his grandson recollecting the Glatstein he knew in childhood and adolescence.

And I love this 1926 photo of Glatstein (on the right), in the Polish spa town of Nałęczów. (Courtesy of Monica Adamczyk Garbowska, through In Geveb.)

Before we get to today’s poems, I also wanted to share another upcoming event for paid subscribers. I had a great time chatting with many of you at the last of these programs, a Zoom talk about the history of Yiddish literature. On Monday evening, 3/27, at 7:00 pm EST, we’ll have an informal Zoom discussion and reading about New York City in Yiddish poetry. I’m really looking forward to this: we’ll consider Yiddish poems that present New York as a place, a character, an idea, and chat about New York as a historic Yiddish literary scene. All paying subscribers will get a Zoom link - it would be great to see you there!

Soon Enough

Soon we’ll have forfeited all words.

The stuttermouths grow silent,

the heritage-bag is empty. Where should we find

the holy babble of our destined

joy? The child's winces

are a foreign tongue of spite

and in the dark we write

a lightning-language that is doused.

And ash becomes its meaning.

And ash becomes its meaning.Only a Voice

For you I will become only a voice,

so that my quiet bones don't scare you

in the valley of ash, of burning.

My words will come to you

in joyous recognition,

awakened and alive as song.

Time's rusty bell

has not drowned them out,

neither their rhythm nor their melody.

Speech bodiless,

although immersed in that

which never fades away,

just like how you remember me.

Listen closely to the voice.

Joy comes from chains of longing.

From bundled flames,

the longing of emergences--

their joy, their joy.I wanted to put these poems side by side, although they’re not side by side in their original setting, for a few reasons. They share a concern with language, of course—with language in a time of destruction and civilizational collapse, language at and after the apocalypse. But what really spurred me to think of these together was the way their endings echo each other: each of these poems concludes with a phrase or a sentence repeated twice. In one we have the brutal, haunting refrain of and ash becomes their meaning, and in the next the doubled their joy, which hints at the possibility of redemption and linguistic delight even (or maybe especially) in the aftermath of catastrophe.

The first of these poems, “Soon Enough,” seems on one level to be about the situation of Yiddish, and of Jewish language in general, after the violence of the Holocaust, and the rupture it caused between the post-war world and the pre-war Jewish civilization in which Glatstein was raised. “The heritage-bag is empty”; the lineage which sustained the spiritual and cultural values of European Jewish life now seems worthless, and all the words that emerge from it are nothing but ashes. The presumably Jewish child mentioned here speaks only foreign languages (and think of this alongside Glatstein’s grandson’s inability to understand Yiddish, and Glatstein’s own son’s inability in the language, mentioned in the video above.)

The next poem is more optimistic. Joy can still emerge from Jewish languages, and can emerge even from the fires that threatened to consume them. “Time’s rusty bell has not drowned them out” — what a striking image of persistence through the devastation of years.

Although this poem is a little bit less clear to me. Who is the “you” to whom it speaks? If you have any thoughts, I’d love to hear them. But I’m inclined to read it as an address to the Yiddish language itself. The poet promises the traumatized language that he will not abandon it, that his words will occasion a joyous recognition, a homecoming, as the language reunites with its words. Of course, I’m open to other interpretations.

Each of these poems arrives at a different conclusion about the possibilities of Jewish language and Jewish spiritual-literary creativity amidst the 20th century’s upheavals. One is bleak, the other alive with hope and possibility. But I don’t want to see these poems as contradictions in need of reconciliation. I’d rather see them as two sides of the same coin, as a great Yiddish writer’s reckoning with his simultaneous grief and apocalyptic despair and optimism and belief in the endless, self-renewing power of the Yiddish word.

Hasn’t anyone who cares deeply about art, and lives in our consumerist society, felt both of these ways at some point, maybe even at the same time? As if “the heritage-bag is empty,” and whatever “lightning-language” of creativity we can find is doused as soon as it sees the light of day. And nevertheless, “time’s rusty bell” can’t overpower everything about the spiritual and artistic power of the past, or the potential of the future. The joy of art is still alive within a mechanized and materialistic society; the joy of the Yiddish word persists after the destruction of much Ashkenazi civilization.

Neither the destruction nor the joy cancel each other out. They exist, each vivid and true, and in the beauty and honesty of Glatstein’s writing we find the culmination of what poetry can offer: a way of expressing intense and contradictory experiences without the compulsion to reduce them into a single narrative, a unified takeaway. Perhaps the contradiction is the unified takeaway.

I’ll admit that I sometimes despair—as Glatstein seems to here—at the debasement of language, Jewish and otherwise, in our culture. So I’m grateful that someone like him, who is well aware of and doesn’t deny the abject awfulness of that debasement, also provides us with a powerful expression of joy, a whole-hearted statement of language’s abiding ability to convey delight and meaning, through both the content and the aesthetic pleasures of his poetry.

Thanks for reading, I’ve you made it this far—I hope you have a freilikhn Purim next week! Things have been unexpectedly hectic for me lately, but I’m looking forward to getting back to a more frequent and regular schedule for this newsletter.

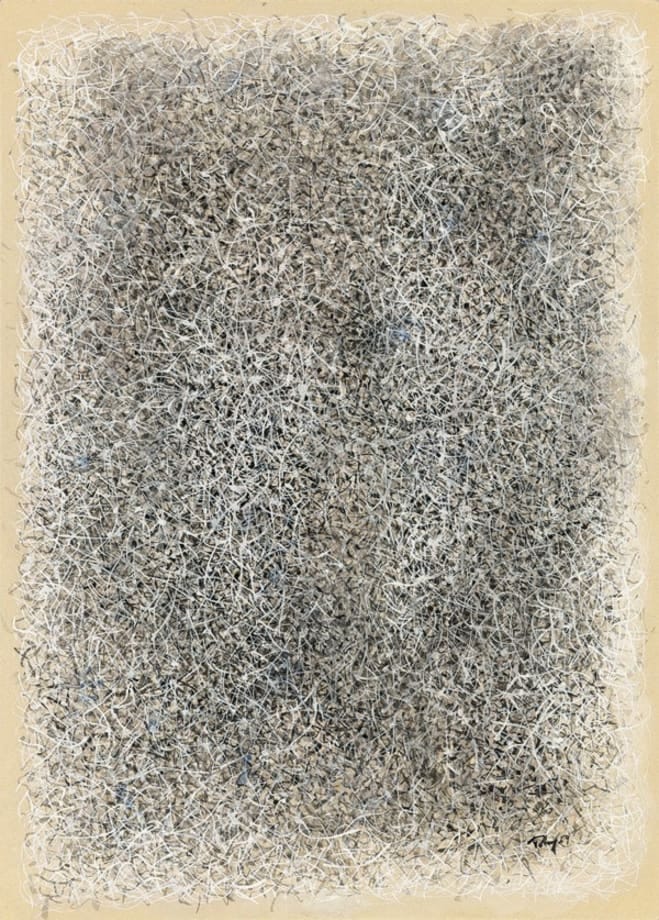

In conversation with today’s poems, here are two of Mark Tobey’s “White Writing” paintings, from the 1950 and ‘60s.